Introduction

In military and industry circles, it is very common to hear technology promoted as a joint and interoperable capability without much attention being paid to the people employing those capabilities. No matter how much faith we have in our technological solutions, resilient architectures must always consider, ‘what if a capability is easily denied or disrupted?’ As decisions in warfare are often driven by human endeavours, viable capabilities that enable Air-Land Integration (ALI) and interoperability must be entrusted to a knowledgeable and united joint force. Simply put, technology alone will not make a joint force interoperable; the people will. Since the article ‘ALI – NATO’s Strategic Joint Challenge’1 was published in September 2019, both Allied Air Command (AIRCOM) and Allied Land Command (LANDCOM) have achieved marked progress in addressing the canyon-sized gaps that prevent ALI from being interoperable between their respective components. While initial joint discussions have been productive, there is still extensive work ahead towards achieving all joint ALI objectives, thereby driving the purpose of this article. Given the vast scope of ALI and the interoperability matters, this article will focus on some promising joint collaboration efforts, outline affordable, practical options for immediate joint action to improve ALI, and present an innovative solution to achieve effective joint ALI and interoperability, which could inform reorganization talks of NATO forces in upcoming summits.

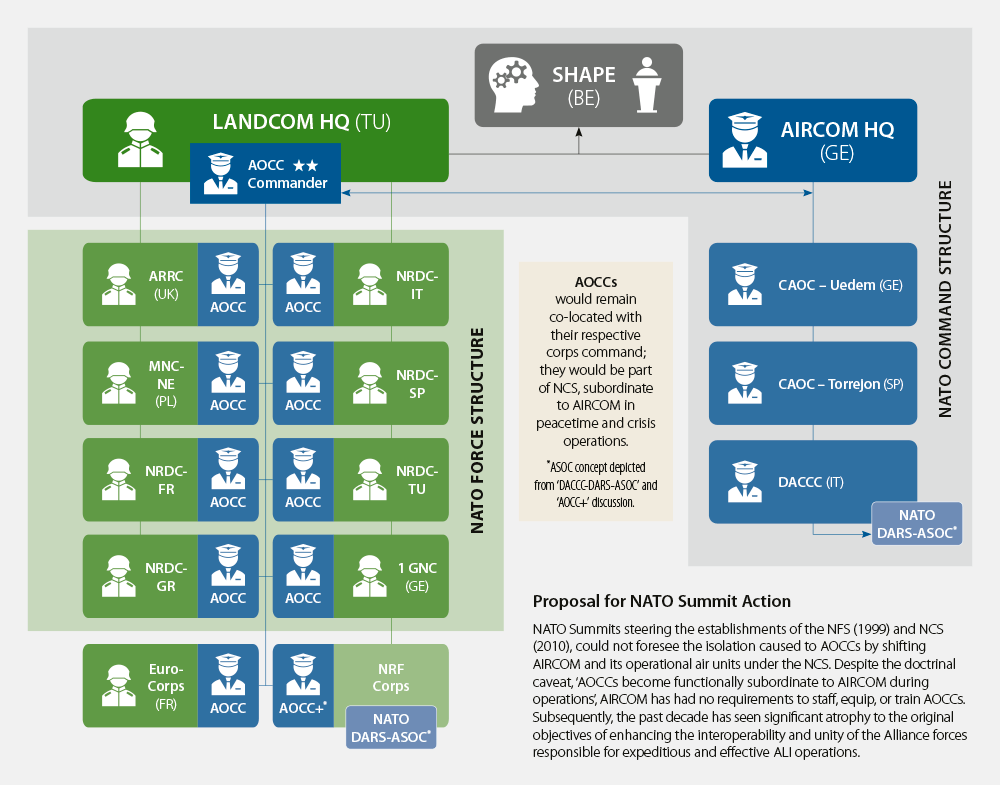

Proposal for NATO Summit Action.

© JAPCC

A Review of Measured Progress

Following the Joint Analysis and Lessons Learned Centre (JALLC) report on NATO’s capacity to conduct ALI, AIRCOM and LANDCOM acknowledged the limitations identified by establishing a joint, two-star led ALI steering group. This signalled the start of a purposeful collaboration between the two components to bridge the fundamental gaps required for ALI to function in NATO.2 The first discussions proved productive, resulting in an agreement to have a permanent Land Liaison Element established at AIRCOM HQ. Given the proximity and participation in the joint steering group discussions, the United States (US) Army Europe 19th Battlefield Coordination Detachment offered a small team to begin immediate land liaison functions within AIRCOM HQ. This has permitted an interim bridge for the two components while this agreement formalizes it into the enduring NATO institutional framework. While establishing permanent liaison positions in each component HQ is a vital step, it is equally important that these two-star level meetings continue to occur regularly to build on the momentum of these early initiatives and to achieve the goals of ALI.

Tactical Options in NATO

While the establishment of an ALI steering group and a Land Liaison Element in AIRCOM are swift and straightforward actions, the JALLC’s Joint Analysis Report, titled ‘Air-Land Integration: Extending NATO’s Tactical Air Command and Control Capability to the Corps Level’, has led both HQs to focus efforts on a tactical solution, which is establishing a NATO Air Support Operations Centre (ASOC).3 A common capability to both US and United Kingdom (UK) militaries, the ASOC is employed as the primary control agency for the execution of air operations in direct support of land operations.4 Its primary mission is the procedural control of air operations within the assigned airspace, short of the fire support coordination line and up to the Coordinating Altitude.5 As an air component asset, the ASOC is subordinate to the Combined Air Operations Centre (CAOC) of the Combined Forces Air Component Commander (CFACC), although, it is located with the supported senior-warfighting land echelon.6 Given its proven abilities over the last 20 years of coalition combat operations for joint fires coordination, responsive re-tasking, and accelerating Close Air Support (CAS) to coalition troops, it is understandable why establishing an ASOC has become a preferred tactical option to enable ALI within NATO. While establishing a NATO ASOC is a reasonable start, it may only exist as a frail and fleeting entity if the durable foundation of standardized joint force education and training is not put forth to support it.

SHAPE’s Zero-Sum Game

Taking into account the geopolitical milieu of NATO members reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic and the abrupt exodus from Afghanistan, it is unlikely to gain favour for funding acquisitions of unproven military-specific technology. With this in mind, there is merit to SHAPE’s zero-sum requirement for AIRCOM and LANDCOM to pursue the development of an ASOC-like capability organic to NATO. While a zero-sum requirement may seem daunting, there are several existing prospects that could meet SHAPE’s directive. More importantly, there are several that could best contribute to laying the durable foundation for joint force education and training, much faster and cheaper than setting up an ASOC. The following sections examine potential and existing ALI capabilities within the NATO Command Structure (NCS) and amongst European-based alliance assets.

A DACCC-DARS-ASOC Option

Since an ASOC is an air component agency designed to enable de-confliction and integration of combat air support to the land component, AIRCOM’s Deployable Air Command & Control Centre (DACCC) has been tasked with exploring the possibilities of standing up an ASOC. Given the mobile airspace control capabilities of the DACCC’s sub-unit, the Deployable Air Control Centre, Recognized Air Picture Production Centre & Sensor Fusion Post (DARS), it is appropriate that it be considered a prime candidate to either re-role or add the ASOC mission to its capabilities profile. The reasoning is that DARS is mainly staffed with airspace controllers and battlespace managers who could most easily transfer their skills to support the procedural controlling functions essential to an ASOC. As it stands today, adding the ASOC mission, instead of a re-role, would limit the extent to which DARS could support and train with the nine land component corps in the NATO Force Structure (NFS). If this DARS-ASOC option materializes, AIRCOM should coordinate prioritization with LANDCOM to support the designated NATO Response Force (NRF) corps. Ideally, this alignment would bolster standardized joint education and training of the NRF forces to exercise and develop Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs). After all, ‘the NRF is a driving engine for NATO’s military transformation’.7

UK’s ARRC: An Advocate of ALI Developments

Given that the UK maintains and trains its own ASOC capability, the UK’s Allied Rapid Reaction Corps (ARRC) has been LANDCOM’s lead to collaborate with AIRCOM on developing options to grow and sustain NATO’s own ASOC capability. This joint collaboration has taken on a new significance for the ARRC, since it was identified to lead as NATO’s first warfighting corps since the Cold War, effective 1 January 2020.8 The ARRC has been trailblazing ALI improvement efforts by working to apply and adapt Joint Air-Ground Integration Centre (JAGIC) US doctrine with the UK ASOC, its Air Operations Coordination Centre (AOCC), and Joint Fires Support Element (JFSE), modelling the potential NATO AOCC+ concept. The JAGIC is a joint seating arrangement that co-locates air and land operators, Command and Control (C2) systems, and decision-making authorities to facilitate rapid and effective mission execution while managing risk through increased situational awareness.9 These efforts and lessons learned should continue to feed into the ALI steering group to identify the requirements to achieve benefits of expediting and synergizing effects by air and land forces.

USAFE-TACP: Bonus Option

Provided that both AIRCOM units and US Air Forces in Europe’s Tactical Air Control Party (USAFE-TACP) work for the same commander, it is logical to consider including USAFE-TACP as another enabling contributor to NATO’s ALI improvement efforts. It is mutually beneficial for NATO units and USAFE-TACP members to regularly train together and share their ALI expertise with an emerging NATO ASOC capability. Particularly, since USAFE is re-establishing its ASOC capability in Poland, under the 4th Expeditionary Air Support Operations Squadron (4 EASOS). For example, in June 2021, the 4 EASOS participated in Slovenia’s premier CAS exercise, Adriatic Strike, paired with a multinational land fires team to showcase the benefits of ALI operations by employing a co-located joint fires C2 team. Furthermore, the TACP instructors from the 4th Combat Training Squadron could be leveraged into promoting joint education and training by conducting mobile training team events to enhance NRF training. Over time, this type of consistent collaboration would grow a knowledgeable network of joint forces that would ultimately strengthen NATO’s ALI.

USAFE-AFAFRICA Warfare Centre (UAWC): Reliable Enabler

Understanding that joint education and training is fundamental to the progress of ALI in NATO, the newly designated UAWC, formerly Warrior Preparation Centre, debuted its ASOC-trainer during its premier joint-combined live, virtual, and constructive exercise, Spartan Warrior 21-9. Given the substantial efforts involved with exercise design and execution, UAWC’s ASOC-trainer would be another mutually beneficial asset in streamlining joint-combined education and training for the Alliance. Not only could it serve as an experimental lab for joint experts charged with developing doctrine for NATO’s own ASOC capability, it could also serve as a live training node, networked to support exercises, such as, but not limited to, AIRCOM’s Ambition and/or NATO’s Joint Trident series. Moreover, if network accessibility is made available to connect the ASOC-trainer to AIRCOM, and other relevant NATO organizations, joint training audiences would benefit from experiencing a more holistic picture of the planning and coordination requirements necessary for actual joint operations. The ALI Steering Group should leverage existing joint education and training capabilities of the UAWC to better, and more affordably, prepare its ALI capabilities for large-scale combat operations and improve the interoperability of the allied joint forces.

Unifying ALI for NATO Joint Forces

A shift in perspective to address joint solutions by means of people is in order, and it can have maximum benefits coming as a result of a NATO Summit decision. While there have been some voluntary collaborations amongst units in the NCS and NFS, the current command relations’ hierarchy does not mandate, nor facilitate, a normalized solution that fosters joint personnel interactions between the two structures. More specifically, what was intended to bring joint forces together is actually perpetuating the divide. The creation of the NCS, an outcome of the 2010 Lisbon Summit, has inadvertently stifled any obligation for AIRCOM to staff, equip, and train the AOCCs, a standing, yet isolated, air component liaison element, attached to each NATO Corps under the NFS. Consequently, the interests and obligations for staffing, equipping, and training between the AOCCs vary significantly. Therefore, the shift in perspective must seriously consider realigning the responsibility of AOCCs under AIRCOM, otherwise there is risk of the complete regression of NATO ALI interoperability. The last decade of ALI, under the current hierarchy, has stumbled along under the triaged doctrinal pretence that AOCCs become functionally subordinate to the NCS Joint Force Air Component during operations.10 However, the question of how this would actually occur has only recently come to light. A realignment of AOCCs under AIRCOM is not too far-fetched when considering the ‘NATO 2030’ vision, discussed at the 2021 NATO Brussels Summit.11 A realignment would be a way to produce tangible results that cultivate genuine joint force interoperability and support several strategic lines of efforts outlined in the initiative. While this shift would likely not be entirely zero-sum, it would offer a course correction to the intended relationship between NCS and NFS that would pay dividends to benefit future NATO forces and joint operations. To this end, joint interoperability requires that all HQs that may command operations in theatre are staffed, trained, and prepared to a common standard.12

Conclusion

Bridging the gap in joint with force education and training is essential. More specifically to the realm of ALI in NATO, a focus on providing a standardized education and training programme for the corps’ AOCCs, JFSEs and joint liaisons will establish a robust foundation. Standing alone, an ASOC will not produce effective ALI unless the core of joint forces, who will affect it, understand its design, doctrine, and TTPs through joint education programmes before it is practiced in joint training. Investigation into the education of joint ALI elements will carry great value, in dynamic operations, stemming from a common understanding of each component’s capabilities, procedures, and limitations. In view of the most practical DACCC-DARS-ASOC option, the combination of such an element with a dedicated joint educational programme, like the ALI Workshop, would propel a durable joint learning programme while keeping close to SHAPE’s zero-sum requirement.13 Such an ALI enterprise, backed by the ALI Steering Group and a NATO Summit agreement for AOCC realignment, would set the course for improving the Alliance’s joint readiness, responsiveness, and ability to maximize collective defences, especially during resource constraining conditions. In the end, these actions would contribute to the efforts outlined in the ‘NATO 2030’ vision, that unified forces enhance NATO’s collective ability to deter, defend, and win against any attack, in any domain.