Introduction

In 1925, General of the Infantry Hans von Seeckt, then Chief of the Army Command, published a memorandum called the ‘Hufnagelerlass’ condemning the increasing bureaucratization within the Army Command. In the memorandum, von Seeckt sarcastically exaggerated the bureaucratic effort involved in introducing a new horseshoe nail as symbol for very simple business processes in the Reichswehr. In conclusion, he called on responsible commanders to cooperate in reducing the bureaucracy.

Almost one hundred years later, the outcome of military acquisition programs still ranges from major failings, such as the US Zumwalt Class Destroyer with a cost overrun of more than 80% and two decades of program delay,1 to great successes such as the rapid fielding of Germany’s tracked howitzer into a war zone while requiring the Ukrainians to develop a domestic fire control system within a couple of weeks. Experiences from rapid deployment of systems to ongoing operations within NATO countries also demonstrate how quick acquisitions are possible ‘when needs are greatest’.2

In sum, few would disagree that the processes for procuring military systems within NATO countries must be improved. Acquisitions are delayed and often exceed budgets. In some cases, they do not even yield the expected performance. But what precisely should be done? For years, there has been ample evidence for, and attention to, the problems in defence acquisition practices across NATO countries.3 National defence acquisition systems have been perceived to be ‘broken’ for decades.4 Yet despite countless inquiries and repeated improvement efforts, most countries remain stuck in old practices or struggle with alternative approaches, showing only a few promising examples.5

At the same time, the need for NATO countries to improve their acquisition practices has become particularly urgent considering two developments. The first is the current security environment, including the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, and increased tensions in the Indo-Pacific and Middle East. The second is the increasing importance of commercially-driven Emerging and Disruptive Technologies (EDTs) to military-technological superiority. These developments put pressure on the range of capabilities NATO countries must possess to deter and handle threats in the 21st century, and urge the Allies to innovate, acquire, and field leading-edge military technological systems faster, better, and cheaper than geopolitical rivals.6

This the first in a series of three articles intending to reflect on the current state of military acquisition programs and provide a concise set of questions to senior managers with decades of combined experience in military programs. It provides a summary of research on the current state of defence acquisitions and derives hypotheses that will be further explored in the subsequent articles.

A Common Dilemma – The State of Defence Acquisitions

Generally, defence acquisitions are perceived as a trade-off between the three outcome parameters: performance, cost, and schedule. These trade-offs are always in tension and are known as the ‘iron triangle’7: ‘you can have it fast, good, or cheap – pick two’.8 However, existing research and experience give ample evidence, that defence organizations often struggle to get even two.

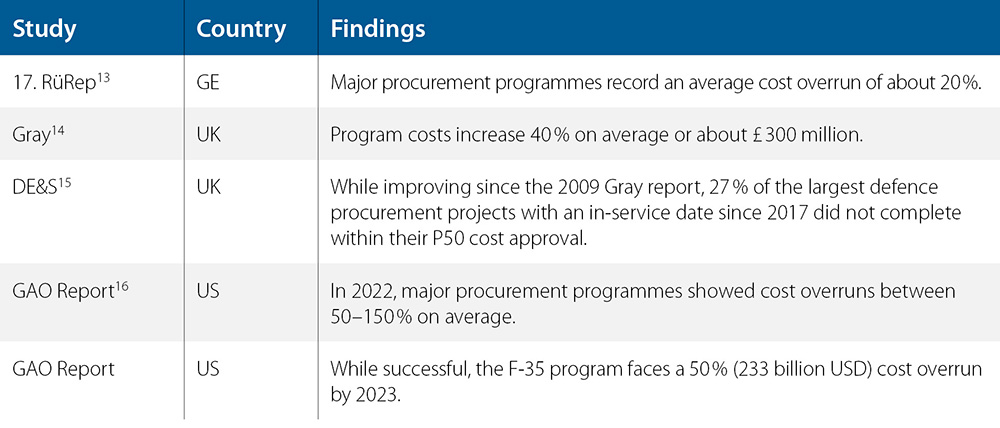

Many studies examine challenges in cost management in defence acquisitions. Table 1 on page 54 shows illustrative statistics on cost overruns in defence acquisition projects. The statistics show how many procurement projects – and particularly major acquisitions – are not completed within budget. The ability to accurately assess costs varies between acquisitions, and novel and/or highly technologically complex materiel make it particularly difficult to calculate costs.9 Furthermore, life-cycle costs tend to be underestimated by government as well as vendor, either due to a lack of data or systematic incentives to underestimate, or both.10

Irrespective of cost overruns, scholars also document how the unit costs of technologically advanced defence materiel have increased between generations of weapon system.11 This puts pressure on defence acquisition budgets. Ultimately, such technology-driven inflation dynamics result in making cutting-edge, technologically advanced military systems less affordable for states.12 The increasing costs of defence material and prioritization of quality over quantity risk creating a ‘technology gap’ within NATO between the most technologically advanced nations and other nations in the Alliance. Moreover, lacking enough depth creates capacity and sustainability gaps, jeopardizing both credible deterrence and the ability to sustain combat.

Main Picture: © tpap8228 – stock.adobe.com; Bullets: © Adobe

Table 1: A sample of cost overruns in defence procurement projects.

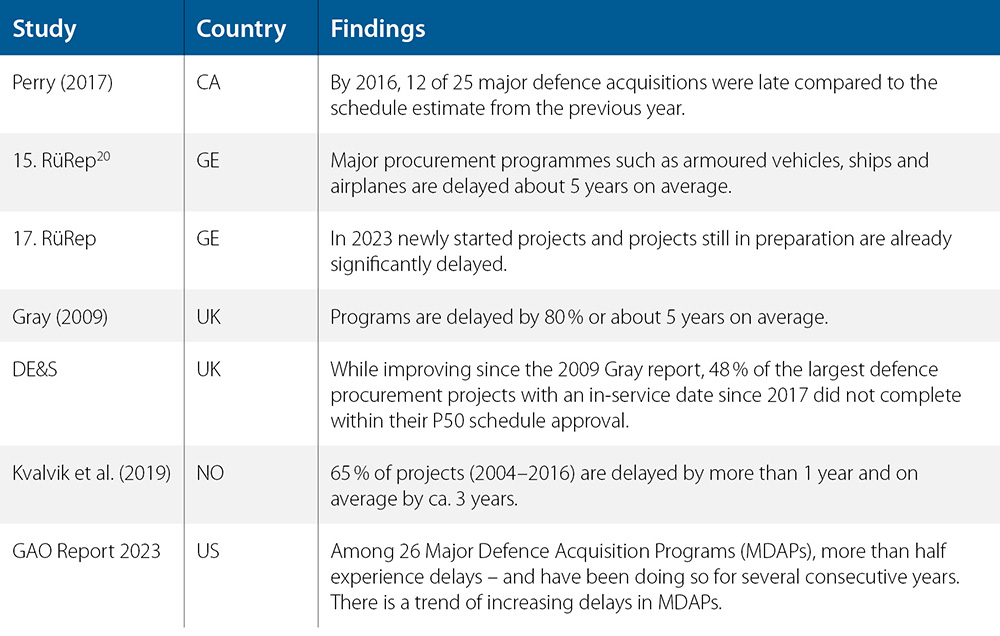

Table 2: A sample of delays in defence procurement projects.

Defence acquisitions are also subject to long lead times,17 and most acquisitions do not manage to complete on schedule.18 Table 2 summarizes statistics on delays in defence procurement projects across nations. It shows how projects on average are typically delayed by 3–5 years with outliers of up to two decades. Even when projects are completed on time, long schedules may still cause challenges. For instance, the former United States Defence Investment Unit Director, Michael Brown, stated that acquisition of major procurement programmes has on average taken 6.9 years from initiation to initial operating capability,19 requiring a long-time span for full capability replacement.

For rapidly developing technologies, such as cutting-edge software and IT, the long lead time coupled with a high risk of delays are particularly problematic. Long schedules and delays also increase problems with responsibility, accountability, turnover among project personnel, and institutional memory.

One major reason for both cost and time overruns in defence acquisitions, is the inclination for over-specification and changing requirements.21 There are no second places in war, urging military organizations to pursue state-of-the-art technology to outperform adversaries. The requirements for system reliability and robustness are also higher in a military context. However, while some systems require cutting-edge technology, other systems would suffice with an ‘80% solution’.22 In such instances, off-the-shelf solutions might exist that could provide sufficient performance, alternatively with minimal adjustments.23

Risk aversion can drive overly detailed or ambitious system requirement specifications.24 ‘Gold-plating’ has also been a widespread problem in defence acquisitions for decades25 – occurring due to asymmetric expert power by the vendor as well as military personnel themselves, and insufficient mechanisms for external verification of system requirements.26 While risk aversion is a driver of gold-plating, studies also document how gold-plating mainly arises from overly ambitious requirements that privileges the newest and best technology.27 There are also cases of system performance itself being negatively affected by over-specification. One example is Norway’s acquisition of a tailored variant of the NH90 multirole helicopter, where Norway eventually decided to terminate the contract due to persistent underperformance, cost overruns, and significant delivery delays.28

Professor Bent Flyvbjerg introduces a phenomenon he calls ‘survival of the unfittest’.29 He observes how many of the projects that survive through the prioritization and selection process tend to be those that look best on paper. However, those are often also the ones with the largest cost and time underestimation or promises of unrealistic benefits, setting up the conditions for failure once initiated. Yet, it is often difficult for decision-makers to cancel poorly performing projects once initiated, for example due to political pressure or fear of embarrassment.30 Although Flyvbjerg examined civilian (infrastructure) megaprojects, not defence procurement projects, scholars have observed the same tendencies in defence acquisitions, both due to the optimism bias and moral hazard.31

Additionally, it should not be ignored that many defence acquisitions are, in fact, highly complicated undertakings.32 Projects comprise a diverse range of materiel, equipment, and systems. Many new technological systems are also increasingly intricate – both the technologies in themselves, but also the system of systems they are part of and the process of ensuring interoperability across systems as well as Allied and Partner nations.33

In sum, beside political, economic, and industrial influence, defence acquisition programs struggle with over-specification, opposing or overly ambitious requirements, unchartered technological territory, risk-aversion, legal framework, bureaucracy, and diffusion of responsibility, resulting in major delays and cost overruns.34

A Hypothesis – We Can Do Better and Quicker

In recent decades, numerous acquisition recommendations and reforms across NATO nations have been aimed at improving the ability to meet cost, time, and quality targets. Already in the early 2000s, defence acquisition experts recognized the need to move towards flexible and evolutionary acquisition approaches.35 Many have also argued for differentiated, or tailored, acquisition approaches.36 However, challenges persist and defence organizations across (as well as beyond) NATO seem to be stuck in a never-ending struggle to implement changes.37 RAND research identifies multiple root causes, including high turnover, particularly among senior leaders, insufficient incentives and support for tailoring, and insufficient education, training and experience among acquisition personnel to leverage tailored approaches efficiently.38 Lack of institutional memory to learn from past experiences may also impede effective changes.39

The successful avoidance of a majority of the aforementioned root cases can be exemplified with Israeli’s ‘Iron Dome’ missile defence system. It went from the drawing board to combat readiness within less than four years. Following an initial operational capability in 2011, the capability of the system has been constantly upgraded while scaling capacities up to ten operational systems effectively safeguarding Israel’s lower tier air domain.40

Avoiding over-specification by focusing on the threat spectrum on hand, allowing the system to be extendable in the future and following Israeli’s political, economic, and industrial priorities had been key success factors. In addition, close collaboration between user and procurement as well as technical expertise from the United States mitigated technological and programmatic risks.

In sum, despite the well-documented and recurring challenges in defence acquisitions, we put forward the hypothesis that military capabilities can be acquired both faster and better than what is currently the norm. Furthermore, in what has become an impenetrable ‘jungle’ of acquisition challenges and policy recommendations, we believe that the most important – and actionable – policy changes for improving defence acquisitions can be uncovered by homing in on the decades of experience and learning acquired by key defence acquisition experts in NATO. This will be the topic of the second paper.

In particular, we will investigate three key avenues for improving future procurement:

- Increasing the use of phased development step-wise expanding new capabilities.

- Following a more software-centric strategy with open system architectures, digital twins, and agile development processes.

- Empowering acquisition specialists – and particularly leadership. Strong leadership is required to implement new policies and procedures, manage risk, and ultimately bring a new defence acquisition culture to life.

In our second paper, we will evaluate these hypotheses by drawing on insights from interviews with senior acquisition management leadership. The final paper then aims to derive concrete and actionable recommendations to improve future as well as ongoing national and cross-border acquisition programs.