Introduction

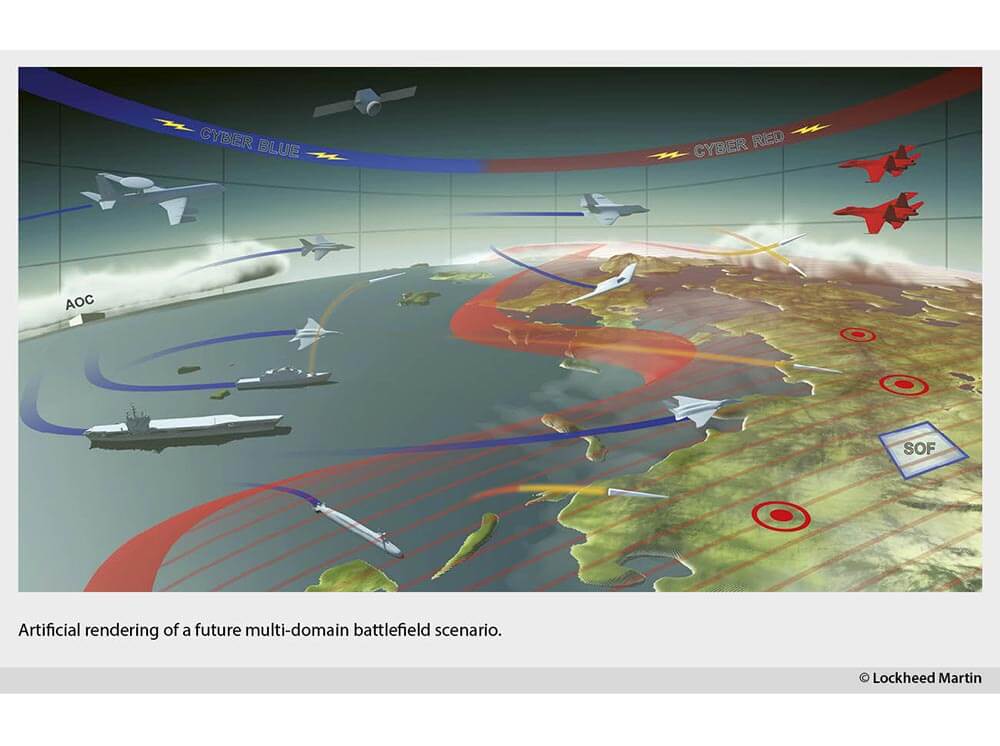

Robust Anti-Access and Area-Denial (A2/AD) structures, coupled with the proliferation of advanced technologies across multiple domains, will dominate the third dimension in the coming decades. Potential adversaries will blend conventional, asymmetric, and hybrid capabilities across each of the traditional physical domains (Air, Land and Maritime) plus Cyber and Space, and will adjust their strategies by utilizing these advancements in an attempt to overwhelm NATO’s strengths. This could compromise NATO’s freedom of manoeuvre, reduce its effectiveness in deterring potential aggressors and undermine stability along the Alliance’s borders. A more comprehensive approach is needed for correctly dealing with these security threats, and effectively operating in this type of ‘multi-domain environment’. It will be fundamental for NATO to develop new strategies that allow a more integrated and synchronized use of forces which can outmanoeuvre adversaries across multiple domains at speed. Recently, there have been numerous papers, studies, and articles proposing a new way of viewing the future battlespace. The previous United States (US) Air Force Chief of Staff (CSAF) General David L. Goldfein, recently summarized his vision in a simple comprehensive concept ‘Victory in future combat will depend less on individual capabilities and more on the integrated strengths of a connected network available for coalition leaders to employ’.1 It is time to embrace a transformation process that leads NATO forces to effectively conduct joint operations across all domains. This will drive the need for advanced Command & Control (C2) systems able to properly connect, integrate, and synchronize forces, regardless of their service or domain affiliation. Systems that can guarantee future commanders the possibility to ‘consider all domains from the beginning of the planning process and be empowered to coordinate dynamic all-domain retasking throughout execution’.2 The future will be characterized by an exponential growth in airspace operations, both in number and complexity; this will pose new challenges to the battlespace management of the Air domain. The purpose of this article is to highlight the importance, for NATO, of developing modern battlespace and airspace management strategies, as the ‘condition sine qua non’ for fighting and winning in the increasingly complex air operations environment of the future.

Seeking Advanced C2 Systems

In a recent report, JAPCC depicts a possible scenario for explaining a future vision of Close Joint Support. In this scenario, a Multi-Domain Command and Control System (MDC2S) will be able to share data with all connected systems across all domains and will process multiple ‘calls for fire’ in real-time. After receiving a digital urgent troops-in-contact message, while considering time-on-target and weapons effect radii, the MDC2S presents a computer prioritized list of available attack options together with the respective Collateral Damage Estimation (CDE) to the Joint Fires Support Coordinator (JFSC). The attack options will include everything from long-range, network-enabled missiles fired from a ship in blue water to artillery and Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRSs), to fixed- and rotary-wing manned aircraft, to overhead, long-endurance Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) with on-board payloads able to be directly controlled by ground units.3 JAPCC’s study anticipates the search for a new approach to combat operations; an approach that can enable forces to plan and execute operations rapidly, but above all, using the capabilities offered by all domains in a synchronized, cooperative, and efficient manner. Indeed, more than the speed of the war platforms, in future fights, the rapidity and the way the commanders at all levels will understand and visualize the battlespace, will be a determining factor for victory. To win future battles, the speed and availability of information sharing will be crucial to accelerating the decision-making process, exploiting the initiative, and creating a position of relative advantage. Current decision-making, planning, and execution processes seem to be slow and predictable. Competing with future peer adversaries will require advanced battlespace management concepts to facilitate rapid synchronization of efforts to create dilemmas for adversaries. This will require ‘continuous and iterative near-term tactical planning, longer-term operational-level planning, and refinement as conditions change’.4 Focused on this need, the US CSAF presented the necessity for an enhanced C2 system. A system that is capable of improving situational awareness, speeding up the decision-making process, and providing a refined capability to direct forces across multiple domains. Following this senior officer’s request, the US Department of Defense (DoD) started a new initiative called Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2). JADC2 could be defined as a new battle management vision. A vision in which future forces will be characterized by the capability ‘to support operations in a highly contested fight, ensuring not just cars, but aircraft, munitions, satellites, ships, submarines, tanks, and people are at the right place at the right time prosecuting the right target with the right effects, in seconds’.5 With this initiative, the DoD is stating that it is no longer the time for developing domain-specific solutions. It is time to think about, develop and adopt a network-centric approach to connect each sensor from every domain with any shooter. In line with this, the ‘Mosaic Warfare’ concept is being developed by the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). ‘Mosaic Warfare’ can be described as a revolutionary new warfighting platform built upon an interconnected and interoperable force package, able to leverage the best characteristics of different platforms.6 A kind of ‘system of systems’ characterized by dedicated new interfaces, communication links, and precision navigation and timing software that will allow platforms to work together. It is based on the concept, that ‘everything that has a sensor could be connected to everything that can make a decision, and then to anything that can take an action’.7 NATO should leverage the possibilities offered by new technologies and develop advanced battle concepts that will enable future commanders, at all echelons, to understand the battle rapidly, direct forces faster than the enemy, and deliver synchronized combat effects across multiple domains. As recently postulated by General Goldfein, ‘The goal [is to] produce multiple dilemmas for our adversaries in a way that will overwhelm them … an even better outcome … is to refine Multi-Domain Operations [MDO] to the point where it produces so many dilemmas for our adversaries that they choose not to take us on in the first place.’8

New Challenges for Future Airspace Management

The above mentioned innovative conceptual battlespace-management models have one thing in common: the use of the third dimension. These concepts will work only if an adequate airspace management system guarantees the commanders rapid and flexible tactical execution through a fast re-tasking of assets, and the dynamic apportionment of airspace. This will require revised airspace management focused on an innovative approach that can guarantee dynamic, real-time airspace coordination while ensuring an adequate level of traffic de-confliction. The situation gets more complicated when considering that the usage of the airspace by all actors will increase significantly in the future, resulting in exponential growth of airspace operations. During the forecast period 2019 to 2026, for example, the usage of UAVs in military operations as well as civil and commercial applications, is expected to grow at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 15.8%.9

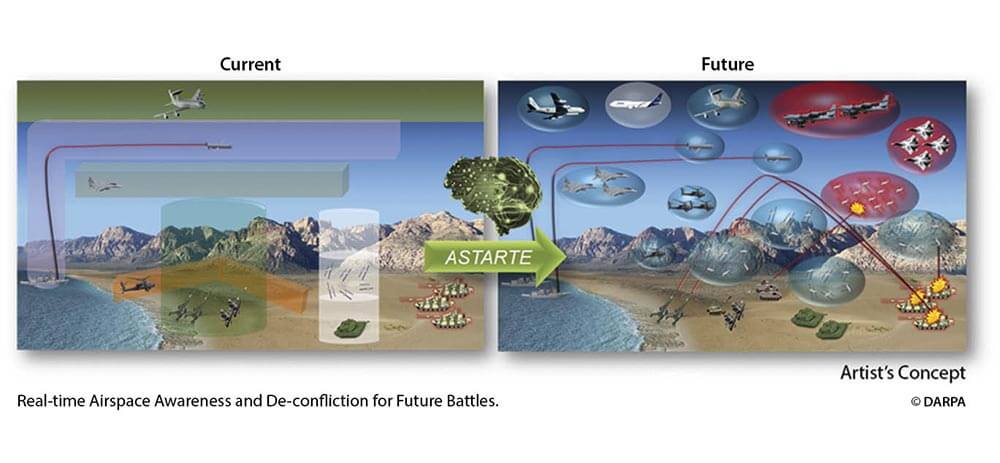

Moreover, all services are developing long-range, precision-guided ‘multi-domain’ weapons, which will drive the need for tighter joint management of the airspace. To highlight a few of these new systems, the US Navy is fielding a new Electromagnetic Railgun, which would be able to zero in on targets from 100 nautical miles away and fire a solid metal slug that could travel at speeds of 4,500 miles per hour.10 The US Army is developing the long-range hypersonic weapon, a rocket-powered boost-glide missile whose expected range is classified but could easily be thousands of miles. The US Army is also pursuing a strategic long-range cannon, a supergun using gunpowder to launch guided projectiles over one thousand miles.11 Futuristic hypersonic weapons, which promise to cross more territory in a shorter time, will break the traditional norms of long-range weapons, including the maximum altitudes reached. Furthermore, it has to be considered that changes in the A2/AD environment coupled with adversary advancements in Cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum, will limit the use of conventional aircraft tracking systems and will drive the growth of demand for stealth platforms. Managing airspace in the near future will become more complex than it is today. Anticipating the future vision of airspace management which is able to face such a complicated scenario, DARPA launched a new initiative for a programme named Air Space Total Awareness for Rapid Tactical Execution (ASTARTE). ‘The goal of the ASTARTE Program is to provide real-time, low-risk de-confliction between airspace users and joint fires to enable support to tactical units and build a resilient air picture under an A2/AD bubble while conducting JADC2 operations … It will interoperate and coordinate with existing C2 systems to ensure airspace users and operators have the most current and relevant information available.’12 Even if only focused on the airspace above an Army Division, (a block of airspace approximately 100 km by 100 km, from the ground up to 18,000 feet) DARPA leads the way for a project that, if fielded, could radically change the current concept of airspace management and make a difference in planning, and conducting future battle strategies.

Interoperability: A Long-Standing Problem

The operating principle of these new battle and airspace management initiatives is mainly based on the possibility offered by leveraging technologies to connect all the available sensors and to process the related data by using artificial intelligence. The Director of the JAPCC and Commander, Allied Air Command, (Ramstein Air Base, Germany), General Jeffrey L. Harrigian, warns, that ‘sensors exist across every domain, but connecting those sensors remains challenging’.13 The current situation, in NATO, contains a plethora of different systems, and sensors, that do not guarantee an adequate level of interoperability. ASTARTE promises to solve this issue by adopting new algorithmic solutions designed with an Application Programming Interface (API) that enables easy integration and interoperability with the full range of currently existing US military C2 Systems.14 Perhaps, the moment has arrived for the Alliance, to make wide-ranging holistic political-military changes that can address and solve the long-standing problem of interoperability, keeping in mind that ‘interoperability does not necessarily require common military equipment. What is important is that the equipment can share common facilities, and is able to interact, connect, and communicate, exchange data and services with other equipment.’15 DARPA’s initiative with the ASTARTE project aimed at obtaining an API that integrates and makes the different C2 systems currently in use interoperable is undoubtedly something that deserves to be sponsored and supported.

Conclusions

The motto ‘divide et impera’ meaning divide and rule, although of uncertain origin, highlighted a policy dear to the ancient Roman emperors. The strategy aimed at maintaining their territories or conquering new ones, dividing and fragmenting the power of the opposition, so that they could not unify toward a common goal. In reality, this strategy helped to prevent a series of small entities, each with a precise amount of power, from uniting and forming a more relevant and stronger entity. NATO is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 different countries and could encounter difficulty competing with an enemy who shows himself strongly united by the use of the same language, tactics, techniques, procedures, and technologies. Using the motto mentioned above as a warning, NATO will have to be capable of promoting new strategies to ensure that the Alliance’s entities are joined to form a centre of power, ready to provide the military forces needed to deter war ‘et impera’ for a long time to come. To achieve this, NATO must seek innovative C2 systems, able to properly connect, integrate, and synchronize forces from all domains. This will require revised airspace management, too. A new one focused on an innovative approach, able to guarantee dynamic, real-time airspace coordination while ensuring an adequate level of traffic deconfliction. Initiatives such as JADC2, ‘Mosaic Warfare’ and the ASTARTE programme will make the difference if developed and adopted collectively by all 30 NATO Nations. As stated by General Harrigian, ‘as we think about existing and developing sensors, we must connect them to form a cohesive, resilient, and self-healing collective network. Therefore, it is crucial that we build in multi-domain interoperability from early design with any future capabilities.’16 It is time to focus on a common framework by which it will be possible to build the future battlespace management as a comprehensive and integrated solution, creating the conditions to position NATO to fight and win in the increasingly complex air operations environment of the future.