Introduction

In January 1991, the Netherlands deployed two PATRIOT squadrons under Article 4 of the NATO agreement to South-East Turkey in support of operation ‘Desert Shield’. Not long afterwards a third PATRIOT Squadron was sent to Israel, in support of their air defence against Iraqi ballistic missiles. Not more than five days after the initial alert and within 20 hours after take-off of the first wave of mission-essential material and personnel, the first system reported ‘At battle stations’, having relocated 3863 kilometres from their initial readiness positions in West-Germany to sites near the Iraqi border.

The entire operation, from the first alert all the way to redeployment three months later, was only possible because the troops had an excellent level of training and equipment, which was ready for battle. Looking at NATO’s current capability and the average preparedness level of the Alliance, it appears that we are far removed from that early nineties level-of-readiness. With a focus on Ballistic Missile Defence, we have been neglecting the art of traditional air defence for Ground Based Air Defence (GBAD) units as well as the Air Command and Control (C2) nodes.

NATOs Integrated Air and Missile Defence

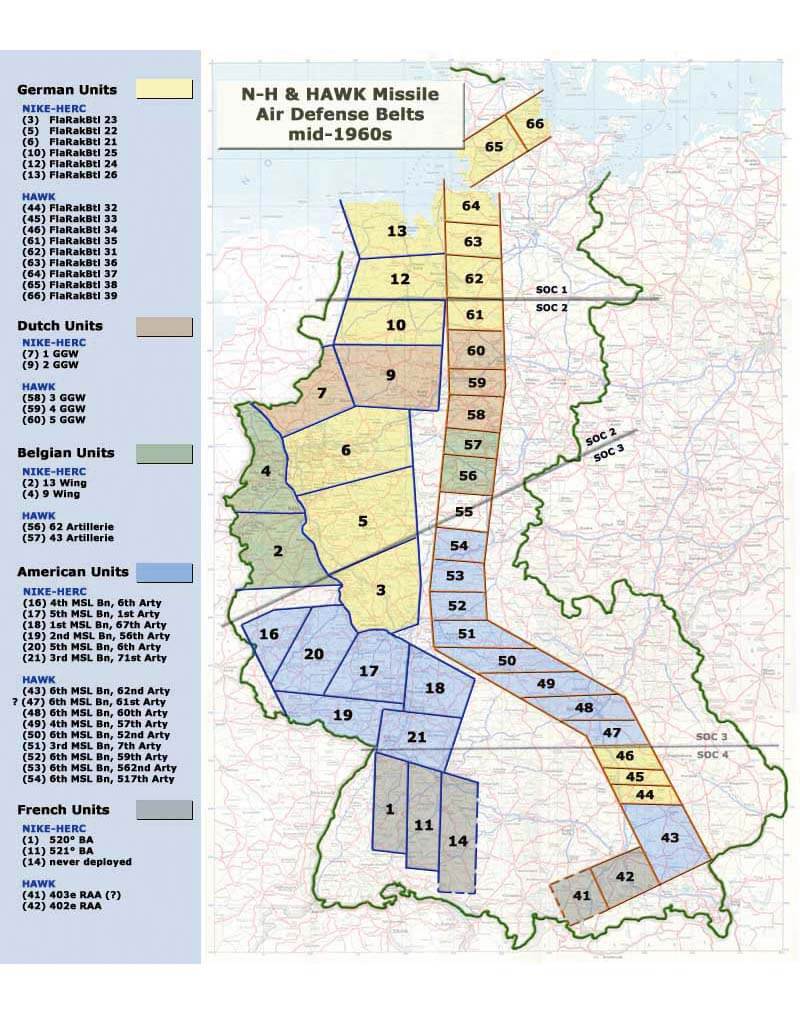

NATO’s defence of Western Europe during the Cold War was structured into areas of responsibility, where the ground forces were responsible for their respective Corps areas and the tactical air defence forces protected the area above them (see figure on page 80). To be able to counter a surprise Soviet (air) attack, air defence forces were at a state of high readiness, 24/7.1

The NATO integrated air defence consisted of multiple layers of different Surface to Air Missile (SAM) systems, combined with air defence fighter aircraft, each in their own designated areas. Coordination took place through very precise procedures, guarded and executed by dedicated Air C2 nodes.

© Copyrighted

After the Cold War, the C2 nodes of NATO’s Integrated Air Defence System (NATINADS) were rapidly dismantled. National C2 nodes shrank to the minimum needed for peacetime operations and NATO kept on reducing its C2 entities until 2011. At this point, an absolute minimum of C2 entities were kept operational to manage the peacetime mission. For NATO’s Air Command (AIRCOM), this meant that from an original nine Combined Air Operation Centres, only two had survived in the entire NATO area and the subordinate C2 nodes were national assets, not necessarily commanded by NATO. It would not be right to just blame NATO, but as NATO mainly provides the C2 backbone and it is the countries that provide the forces, all of the member states just reduced defence budgets and with that their forces. This was a trend that did not break until 2014.2 In general, the European militaries in NATO shrunk from fully capable armed forces, able to counter an all-out threat to Europe (Article 5 scenario), to small independent armed forces providing units only to fulfil a NATO request for troops to support a confined ‘out of area’ operation. In fact, this became NATO policy. Although regularly discussed within military circles, this remained the policy until the Warsaw Summit in 2016.3

Along with these large cuts in C2 nodes, NATO practically doubled its European territory towards the east with the incorporation of new member states joining NATO. In these former Warsaw-Pact countries, first priority for investment and improvements in the area of defence was not the expensive high-tech air defence systems that were commonplace in the west. The resources that were available originated from former Soviet stocks and were in no way technically compatible with the ‘western’ equipment used by the ‘older’ NATO members4. The big exceptions in real NATO capability, are investments in NATO’s Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) and the Air Ground Surveillance (AGS) project. For BMD it is worth noting that this is focused on a specific threat from the Middle East region, dealing solely with ballistic missiles with a certain range, threatening NATO’s European territory. Although BMD is a part of NATO Integrated Air & Missile Defence (IAMD), it is not only an important addition to the capability, but it also brings extra complexity to the air battle and therefore requires integration into NATO’s IAMD training protocols. There were other investments within NATO, but none that expanded existing fighting capabilities and were mainly limited to the replacement of obsolete systems.

It was not until the United States, in 2018, rather explicitly made it clear to their NATO allies that there had to be a better ‘burden-sharing’ (as already pronounced during the 2014 Wales summit)5 before NATO allies started to react, albeit step-by-step. Currently, it is challenging for NATO to perform IAMD within its ‘newly’ (since 1991) obtained territory. The nations of the Alliance still uphold their surveillance and tracking responsibilities though, which together with the AWACS (and the upcoming AGS) is enough to provide full airspace surveillance capability for its area of responsibility. The full system of IAMD not only lacks a C2 capability and air defence resources, but the interoperability challenges NATO faces between these scarcely available resources are quite challenging. It is therefore very important to keep or bring these scarce resources (low quantity) to a high level of readiness and training (high quality), to at least enable maximum efficiency.

New Threats to NATO and Other Wake-up Calls

One of the first omens indicating change was the conflict in South Ossetia in 2008. Torn between a Russian history and a hope for a more western future, a civil conflict offered Russia the opportunity to show that the days when it could be ignored were over. Russia displayed its high-tech weaponry and demonstrated that it was well capable of modern warfare in the air, on the ground, and within the electromagnetic spectrum. Russia was no longer to be kept out of the geopolitical equation. Experts stated that a freeze of the situation at the end of 2008 was the best outcome which could be achieved by the West.6

In Ukraine during 2013, internal differences of opinion over whether to take a western/European course for the country’s future or to remain loyal to the old supporter, Russia, led to a political dilemma. This dilemma led to a conflict in which people in eastern Ukraine (east of the Dnipro River) and the Crimea (the vast majority of people living there are ethnic Russians) stated a preference for Russian governance. On 7 April, Eastern Ukraine declared itself ‘The Donetsk People’s Republic’. Russia in the meantime played its role as a world power, by placing large troop concentrations close to the Ukraine’s borders. During the summer of 2014, a short civil-war for Eastern Ukraine was fought, where Russian military knowledge and power allegedly stopped the Ukrainian offensive and secured the Donetsk People’s Republic. Again, Russia showed it was back in the game.

In the above-mentioned situations in the European region, but more recently in the Syrian theatre, Russia has also demonstrated its twenty-first century, updated-military power by fully integrating joint operations, high-tech weaponry and superb coordination with hybrid warfare tactics. This reinforced Russia as a player on the world stage, which has to be taken into account.

With an underlying terrorist threat, the revival of Russia as a world power, the influence of rapid technological developments in general and an apparent growing instability worldwide, NATO’s security situation has dramatically changed. For air defence specifically, the rapid proliferation of missile technology, (near) future hypersonic threats like upcoming cruise- and glide-vehicles as well as (swarming) drones only adds extra challenges that will require an adequate air defence to answer as well.

In order to cope with the changing situation, NATO needs to adapt. Air defence is a complex technological and procedural part of our defence. Incidents like the downing of Flight MH-17 in Ukraine and UIA Flight 752 in Iran7 showed what can happen when air defence forces are not properly controlled or trained. Air defence is often the first line of defence in a conflict and thus will require high-training standard and readiness.

NATO’s Training Philosophy and the Tactical Evaluation Programme (TACEVAL)

Exercises

A brief look at NATO’s exercise philosophy includes exercises conducted in three forms: a Live Exercise (LIVEX), Command Post Exercise (CPX), or an Exercise Study. A LIVEX is an exercise in which actual forces participate. A CPX is a headquarters exercise involving commanders and their staffs, and communications within and between participating headquarters, in which NATO as well as opposing forces are simulated. An Exercise Study is an activity which may take the form of a map exercise, a war game, a series of lectures, a discussion group, or an operational analysis. NATO’s exercise programme planning covers a period of six years, with detailed programming for the first two calendar years, and outline programming for the following four calendar years.8,9

NATO’s focus in the last twenty-five years has not been on large scale conflict, the traditional Article 5 Collective Defence scenarios, but rather on Smaller Joint Operations (SJOs) at the edges of NATO territory or ‘non-article 5 Crisis Response’ exercises. In general, the assumption was that the adversary would have some military potential, but would always be at a lower level than NATO’s capabilities. It is only in the last few years that NATO has started to look at how it would operate in a so-called ‘near-peer’ scenario and how to operate against an adversary with a similar capability. Exercise Trident Juncture 2017 (Joint Force Command level) clearly demonstrated the challenges accompanying such scenarios. One thing to consider in these scenarios is that numbers do matter, since attrition plays an important part in the campaign outcome. NATO does not seem used to such conflicts anymore, after a time when we could choose the option of ‘low-risk’ scenarios. A near-peer scenario will not offer that option.

Air Power in Exercises

Air defence is an essential part of ‘Air Power’. Air Power in NATO is managed by NATO AIRCOM. IAMD, however, is a joint operation, and so includes assets of the Land and Maritime Command as well. IAMD in joint operations requires solid planning in advance, backed up by well-developed Doctrine, Tactics, Techniques and Procedures. In addition, coordination during the execution of air (defence) operations is absolutely essential. It is obvious that this level of planning and coordination requires solid training.

NATO AIRCOM has a very busy exercise schedule. Looking closely, it reveals multiple smaller exercises that comprise either smaller tactical units or small geographical areas. The exception is the exercise series Ramstein Ambition10, whose objective is to train the AIRCOM ‘war-staff’ on the Joint Force Air Component (JFAC) procedures. This NATO Command Structure JFAC is not a standing NATO organization. It comprises a ‘backbone’ that works its peacetime duties at AIRCOM, but which is dependent on a substantial amount of additional support from throughout the NATO Command Structure, as well as from NATO countries to man and augment the headquarters. As a matter of fact, the majority of possible JFAC’s in NATO are national assets. In essence, NATO AIR has one AIR Command and Control (Air C2) exercise per year. It is clear that the complex art of IAMD performed by a composite JFAC requires more solid training.

Exercises are not limited to NATO initiatives. There are a number of NATO nations that provide outstanding training possibilities in the domain of IAMD. Next to the NATO AIR exercises, NATO C2 entities support or play an important role in (multi-) national exercises of member states. Therefore, for NATO training, access to NATO exercises and Allied (bi- multi-) National Exercises is available. At this moment SHAPE and AIRCOM are showing an increased interest in these exercises as a vehicle for their training objectives.

As mentioned above, NATO Exercise Ramstein Ambition is an excellent venue for JFAC training, however the subordinate unit levels are not involved, although there are a number of national exercises where that level is trained and triggered. The most well-known of these are without a doubt the Netherlands-German initiative Joint Project Optic Windmill11,12 and the Eastern Europe originated SBAD exercise ‘Tobruk Legacy’13. Both exercises, for all their success, are highly dependent on NATO (AIRCOM) support to create a realistic environment.

The TACEVAL Programme

For IAMD units Combat Enhancement Training or Force Integration Training is hardly an option as they will be part of a first line of defence in any conflict. IAMD units need to be prepared and an audit (Tactical Evaluation), announced or not, would be an outstanding verification tool for NATO Commanders.

During the cold war, in order to keep its air defence forces at a high standard, NATO (in 1960) developed the Tactical Evaluation (TACEVAL) system. A standing NATO evaluation team, together with experienced allied subject matter experts, regularly checked the readiness, resources and training standards of NATO’s units. Next to air defence capabilities, this evaluation also included Force Protection (Survival-To-Operate) and Logistical Support. The Air troops consisted of: Air Command and Control units (Air Surveillance and Control System); flying units (NATO commanded airfields on the West-European continent); and all Ground Based Air Defence Units in the SAM belt.14 After the Cold War, as NATO decreased its NATINADS, the TACEVAL branch shrank as well. However, TACEVAL maintained a minimum capability within AIRCOM. Although mandatory for all forces offered to NATO, not all of these forces are currently NATO-qualified or are undertaking this evaluation. The strength of a TACEVAL team is that it serves as an audit team for SACEUR. It provides a substantiated finding of the state of NATO’s tactical air forces, or at least those elements that were offered for evaluation. The days when all NATO command forces could receive an unannounced readiness evaluation and were subject to a yearly tactical evaluation are in the past. This would require a significant expansion of the TACEVAL branch and a mandatory TACEVAL for all forces offered to NATO AIRCOM. Nevertheless, since the certification of the troops offered to NATO is a national responsibility, NATO requires an audit team to verify the status of these troops. The NATO TACEVAL system was created for that verification and with some investment could easily serve as NATO’s audit team. An audit team is an essential part of quality control within any organization.

Assessment

With the significant reduction of forces after the fall of the iron curtain, both NATO and the individual NATO member countries (perhaps spoiled by air superiority in the last thirty years), seemed to have lost focus on the importance IAMD brings to the Defensive Counter Air role. With NATO’s AOR having grown significantly in the years since the Cold War, air defence has become much more important and the focus on its sustainability and standards, particularly regarding IAMD, have been challenged by lack of investment and training opportunities.

Recent events in Eastern Europe and Syria have forced the consideration of another approach for NATO military capabilities.

NATO has training events and capabilities in order to keep its air forces at the NATO standard for all of the out-of-area operations that have taken place in the last three decades. However, in a near-peer scenario, numbers will count for more since attrition in these scenarios is considered normal practise. Since numbers will count again and due to the low number of NATO forces, the quality of our forces will have to make up the difference.

Air defence is a complex technological and procedural part of our defence. A successful execution of the IAMD mission depends heavily on interoperability, connectivity, and a shared common understanding of doctrine, concepts of operation, tactics, techniques and procedures. A complex mission such as IAMD requires extensive training of all entities involved, from the strategic level down to the tactical level. The training will need to be fully integrated, as the battle will be integrated.

For the NATO commanders to watch over the training status of NATO air defence units, a recurring NATO audit is necessary. This also puts more emphasis on each member nation’s own responsibility to provide NATO with well-trained units. The TACEVAL system has been proven as a great tool to verify this.

Proposals and Recommendations

Although the NATO training calendar seems adequately populated, there is a significant need for more joint and integrated air defence training. NATO should reinstate its large scale Joint Force exercises to train Headquarters and unit interactions. In between these Joint Force exercises, Air Command should perform an annual exercise in which the Land and Maritime (SBAD) forces are integrated, since the air and missile defence battle is by definition a joint battle. These annual exercises do not necessarily have to incorporate large troop formations as in a LIVEX (like Joint Force exercises), but they should not be limited to CPX only. A hybrid form where operational level decision-makers are challenged by the execution of their plans by the war-fighters at the tactical unit level, and vice versa, would work well. National initiatives can play an important role in NATO’s AIR training. Exercises like Joint Project Optic Windmill and Tobruk Legacy, but only with the robust (fit to the scenario) participation of the NATO Command Structure, could be a solid basis for IAMD training.

NATO could make use of its proven, ‘old-school’ training capabilities through adaptions to current requirements. The backbone of IAMD is still present in the NATO Command Structure. It will require funding and manpower and will certainly require some time, but NATO is ready for a renaissance of its integrated air defence system.