Introduction

As the Maritime domain is becoming an increasingly complex and contested environment, questions are raised as to how future operations at sea will be conducted and what capabilities will be needed. In this regard, the role of the aircraft carrier has long been debated, as the advancement of weapons systems and other disruptive technologies may hamper its ability to provide Sea Control, Power Projection, and Freedom of Navigation.

Understanding the challenges that navies – and in particular aircraft carriers – will face in the contested global and maritime environments helps identify future roles of these formidable assets, both as extraordinary political instruments and effective military tools.

The Maritime Domain – A Contested Environment

Following the end of the Cold War, western nations may have considered the Maritime domain as an uncontested environment to conduct Sea Control and Power Projection operations in blue and littoral waters unabated. Additionally, with no strategic competitors, NATO and western navies diverted their naval industries towards enhancing their amphibious and maritime security capabilities to counter illegal activities at sea and ensure the Freedom of Navigation.1

Nevertheless, in the 21st century oceans and seas have become the principal arena for strategic competition and naval rivalry, with the resurgence of Russia and the rise of China as global economic and military powers.

Historically, Russia has always placed a particular focus on the Maritime domain. The current Russian naval policy considers the Russian Federation Navy (RFN) one of its most effective instruments of strategic deterrence, either nuclear or non-nuclear.

Currently, the Russian shipbuilding industry seems unprepared to achieve the strategic goal of a complete modernization of the navy.2 Nevertheless, a new fleet of technologically advanced submarines and smaller surface vessels, both equipped with the formidable Kalibr advanced missile system, flanks the legacy Soviet-era units as a testament to the renewed, aggressive posture of Russia’s maritime policy. RFN training and exercises at sea have significantly increased in quality and quantity. Although the number of larger ships has not increased recently, their deployments at sea and ‘show-the-flag’ activities have increased considerably in the last decade. The constant presence of military units in the Mediterranean, the recent combined activity with Chinese units in the Sea of Japan, and the exercises conducted in the Baltic and North seas in the last years demonstrate Russia’s return to the world’s scene of naval competition and its power projection capability.3

Regarding China’s ambitions in the Maritime domain, Yin Zhongqing, National People Congress Financial and Economic Committee vice-chairman, stated that ‘the ocean, deep sea, and polar regions could be developed and exploited’ and that ‘strategically managing the ocean has become the necessary path for China to open up and develop new space, give birth to new economic industries, create new engines for growth, and build new shelters for sustainable development in the new period and a new era’.4

To this end, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has developed the largest naval force on Earth, with 355 ships and submarines of which an estimated 145 are major surface combatants. China is building aircraft carriers and related fighter jets, modern surface vessels, a new generation of submarines, amphibious assault ships, and a fleet of icebreakers. This number is expected to grow to a predicted total of 460 ships by 2030.5

It may be assumed that, if uncontested, the PLAN will be increasingly capable of achieving sea control throughout the seven seas by 2030 and potentially sea superiority by 2049.6

Aircraft Carriers in the Contested Maritime Environment

The traditional advantages of aircraft carriers are impressive: global reach, long-endurance, massive firepower, rapid deployment and re-deployment, and multi-tasking.

Furthermore, the intrinsic value of an aircraft carrier must also be considered from a political and diplomatic standpoint. In times of global aggressive competition, such a powerful asset provides a nation with a tangible and prestigious effect through presence alone. The media impact of its presence in a given area, far from the motherland, and its port visits to both friendly and potentially non-friendly countries magnifies a nation’s global reach and amplifies its power. Aircraft carriers are ‘key forward-based elements of the nation’s deterrent and warfighting force’7 and ‘the most capable offshore military warship mankind has ever built and a symbol of the absolute navy and national strength’.8 From this perspective, the value and relevance of aircraft carriers in uncontested or reduced-threat areas is undeniable.

Nevertheless, in highly contested environments, the reputation of grandeur that has characterized the aircraft carrier since the end of the Cold War would be strongly questioned. Soon, aircraft carriers will have to choose between operating where they can be effective and where they can prevail. In particular, it is conceivable that adversaries’ Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities may prevent entry of a Carrier Strike Group (CSG), forcing it to operate beyond its preferred range, thus ‘denying or degrading its ability to support other military operations’.9

Major topics of discussion among naval theorists revolve around the future roles of the aircraft carrier or, rather, which of the traditional roles are still viable in the light of the changing operational environment and what capabilities are required to compete with the adversaries’ A2/AD.

Rubel R. C., a distinguished military professor at the United States (US) Naval Academy, identified six historical roles for aircraft carriers: eyes of the fleet, cavalry, capital ship, nuclear strike platform, airfield at sea, and geopolitical chess piece.10 Based on historical hit-and-run land strikes, the role of cavalry has largely been replaced by the employment of naval cruise missiles, avoiding the need for aircraft carriers to enter danger zones to perform air missions. Nuclear strikes also pertain to the past, being substantially inherited by land- or submarine-borne ballistic missiles or by long-range bombers.

Consequently, the critical issue of a future role concerns the remaining four missions, which are strongly related to the CSG defence capability and its embarked air wing. The CSG impunity at sea relies on a multi-layered structure, including aircraft and medium- and long-range surface-to-air missiles to counter inbound enemy targets at long distances and point defence systems for short-range engagements. However, due to adversaries advanced A2/AD systems, in the future this three-layer defence system may ‘best be thought of as a strainer, not a shield’.11Therefore, it has been observed ‘that carriers themselves may not be able to move close enough to targets to operate effectively or survive in an era of satellite imagery and long-range precision strike missiles’. It is a common assertion that uncrewed assets, complementing the crewed ones, will most probably solve this limitation. The latter are admittedly necessary for those missions that require a level of human judgment. In addition, ‘the manned aircraft simply is too useful, too adaptable and flexible, to be abandoned’ and their role will remain pivotal in low-intensity operations, such as counter-insurgency, counter-terrorism, or maritime security.12

However, to mitigate the risk of aircraft carrier losses in highly contested A2/AD environments, it will most probably be necessary to embark on large numbers of Uncrewed Combat Air Systems (UCAS), loaded with a diversity of weapons and sensors and able to fulfil multiple missions. Such an option may be the best solution to guarantee the aircraft carrier’s offensive firepower at greater distances and increase its survivability. The United States Navy, for instance, has been testing the X-47B UCAS, an uncrewed carrier-based, long-range strike fighter capable of autonomous aerial refuelling. The system was intended to exploit ‘the full potential of what unmanned surveillance, strike, and reconnaissance systems can do in support of the Navy’ and the possibility of operating seamlessly with crewed aircraft as part of a Carrier Air Wing.13 Eventually, the programme was cancelled in favour of the less stealthy MQ-25 Stingray, an uncrewed autonomous aerial refueller that will extend the combat radius of embarked fighters.14 Nevertheless, the US is revisiting the requirements for an uncrewed long-range striker, particularly after China has recently introduced a stealthy attack drone, the Gongi-11.15

One of the main issues related to uncrewed systems is the level of autonomy, namely the ability to interpret a specific tactical situation and react accordingly. The development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is not yet sufficiently mature enough to resolve the ethical and legal issues to allow a machine to take decisions in ambiguous situations. Given the current technological shortfalls, it is generally recognized that ‘until research is mature enough to coherently implement AI in a broad range of scenarios that military forces may encounter, unmanned systems will continue to be used only under close human supervision’.16

© Airbus

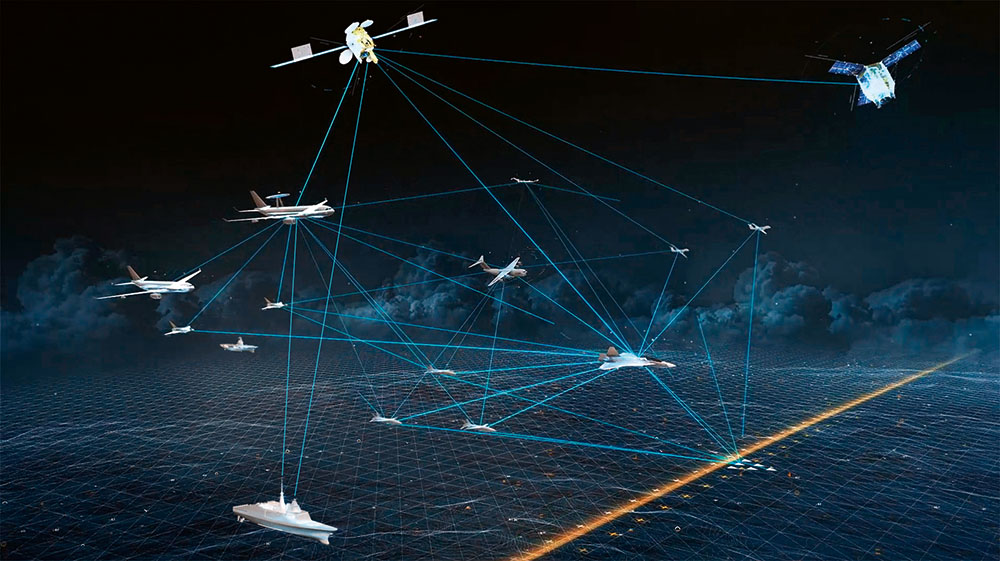

Consequently, the necessity for the CSG to organically Command and Control (C2) crewed and uncrewed aircraft poses another set of requirements. These include robust connectivity and the ability to process vast amounts of data to gain information superiority and outpace the adversary’s kill chain. These requirements fall within the broader concept of Multi-Domain Operations (MDO).

MDO represents ‘a response to a changing competition-space characterized by complex problems that defy current approaches and A2/AD challenges which require more fluidly integrated capabilities across all domains’.17 It focuses on integrating and synergizing capabilities from the maritime, air, land, space, and cyber domains (to include the electromagnetic spectrum and information environment) to expedite the planning and execution processes by analysing large amounts of information at high speed and by connecting sensors to shooters. Future military operations will require the integration of different battle networks in a system of systems to increase the overall operational tempo.

As the maritime environment may well be considered a joint theatre, rather than the natural environment for navies to operate in, current and future scenarios require greater cooperation and interoperability across all domains. Domains’ mutual support will increase the maritime warfighting ability, including the air power. The proliferation of multinational projects, such as the F-35, may enhance prospects towards interoperability.

However, the path to fully integrated domains and capabilities is not free from pitfalls. The current C2 construct is not robust enough to manage the widespread and continuous multi-domain integration at the pace and reliability required for future operations. In addition, the coexistence of legacy and next-generation systems suggests integration and interoperability issues that need resolution. Above all, operations will require synergy between services, jointness across multiple domains, and improved interoperability between nations and the Alliance.

The need for NATO to operate synergistically across all domains is paramount. Understanding how the CSG will fit in future multi-domain operations will allow it ‘to survive against a peer adversary, and remain a viable, valuable asset in the Joint Force Commander’s portfolio’.18

Conclusions

The Maritime domain will undoubtedly be a principal stage for strategic competition in the future. Advanced weapons systems – and the proliferation of disruptive technologies by state and non-state actors – have increased the risks to freedom of navigation and global trade and pose a severe challenge for maritime security in the open seas and littoral regions. Furthermore, the development of a more aggressive naval policy by NATO’s strategic competitors requires an effective naval instrument capable of guaranteeing Sea Control in areas of strategic interest.

Among all military instruments of naval power, the aircraft carrier and its embarked aircraft have been pivotal for decades. While the political and diplomatic roles of the aircraft carrier remain unchanged in a contested, yet peaceful environment, current threat systems have undermined its perception of invulnerability. This may require an adaptation of their traditional roles and missions. Moreover, the proliferation of anti-access systems emphasizes the need for innovative concepts – such as MDO – to maintain superiority at sea. By exploiting full integration, interoperability, and synchronization across all domains, NATO navies can increase the effectiveness of crewed and uncrewed aerial systems and operate with greater lethality from safer distances.

There is no doubt that nations and their navies will continue to value the political, military, and economic power associated with aircraft carriers. Nevertheless, work remains to ensure their viability against current and future high-end threats.