Introduction

In the dynamic and ever-evolving strategic landscape, NATO continually adjusts its Military Instrument of Power via the ‘Concept for Deterrence and Defence of the Euro-Atlantic Area’, and the ‘NATO Warfighting Capstone Concept’.

As a military Alliance, NATO’s primary objective is to provide credible deterrence and defence, recognizing deterrence as the most effective means of preventing future conflict. It is essential for the Alliance to eliminate any doubts – both among NATO’s allies and our adversaries – regarding NATO’s readiness and commitment to safeguard every inch of the Alliance’s territory. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has underscored the urgent need for NATO to enhance its readiness in order to deter potential adversaries. Consequently, the Alliance is actively reviewing and developing strategic documents and plans that have wide-ranging implications for NATO. These initiatives are designed to enhance NATO’s availability, readiness, and resilience across all domains.

This article will specifically focus on readiness in the Air and Space domains, highlighting their significance as critical factors for NATO’s defence and as powerful tools for deterrence. However, the scope of this article is limited to the readiness lessons identified from the Russia’s aggression against Ukraine (RUS-UKR war).

Readiness

One of the fundamental lessons imparted to soldiers upon joining the military is the imperative to be prepared for any situation, at any time and in any location. This principle of readiness remains relevant across all aspects of military forces.

Among the various definitions used throughout the Alliance, the US Department of Defence offers a comprehensive definition of readiness as the capability of its forces to ‘fight and meet the demands of assigned missions’. This encompasses both the ability to swiftly deploy forces and the capability to sustain them once they are deployed. NATO, in assessing readiness, employs a range of metrics such as troop availability, level of training, and the condition of equipment, including enablers.

The ongoing unjustified and illegal aggression by Russia in Ukraine underscores the critical importance of NATO’s readiness. Consequently, the Alliance has augmented the size of its rapid reaction force, known as the NATO Response Force, and has devised efficient mechanisms to swiftly reinforce from North America and mobilize forces within and across Europe. Additionally, NATO is actively striving to enhance the interoperability of its forces, enabling them to collaborate more effectively.

NATO’s readiness plays a vital role in preserving the ability to deter aggression and defend member states. By maintaining a high level of readiness, the Alliance fulfils its defensive obligations and deters potential adversaries from engaging in any form of aggression.

NATO’s Air-Domain Readiness

Airpower possesses inherent strength through its combination of speed, reach, altitude, agility, and concentration, creating multiple dilemmas for adversaries. To harness these capabilities effectively, NATO’s Air Power must be prepared to engage in combat and fulfil assigned missions and tasks. This entails defending NATO forces, populations, and territory from threats originating from all strategic directions, safeguarding the integrity of airspace, demonstrating Allied solidarity, and reassuring NATO Allies.

Preparedness for NATO Air Power operations, as an integral part of readiness, necessitates well-maintained equipment, proficiently trained personnel, and the ability to deploy at the right time and place. To meet these requirements, NATO has consolidated some of its competencies through the NATO Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD) system. This system provides a highly responsive, robust, time-critical, and persistent capability, enabling the Alliance to maintain desired control of the assigned airspace and carry out a full range of missions in peacetime, crisis, and conflict. NATO has already made significant strides in enhancing the readiness, awareness, and responsiveness of its IAMD forces, ensuring the availability of appropriate capabilities.

The NATO IAMD system serves as the foundation and backbone for a prepared and capable Air Power that serves to deter and defend. Ongoing efforts will continue to focus on four key areas: enhanced Air Policing, combat training, force integration and interoperability, and comprehensive training and exercises. Considering the adversary’s initial activities in armed conflicts often involving missile strikes as witnessed during the early stages of the Ukraine conflict, the NATO IAMD system is critical in the current strategic environment and must always remain available. Consequently, substantial collaborative efforts are required. The most visible aspect of these efforts is Air Policing, where continuous airborne surveillance and fighter patrols represent a significant step forward as a ‘show of force’ compared to the pre-Ukraine conflict era, not only as a demonstration of force available but also of readiness.

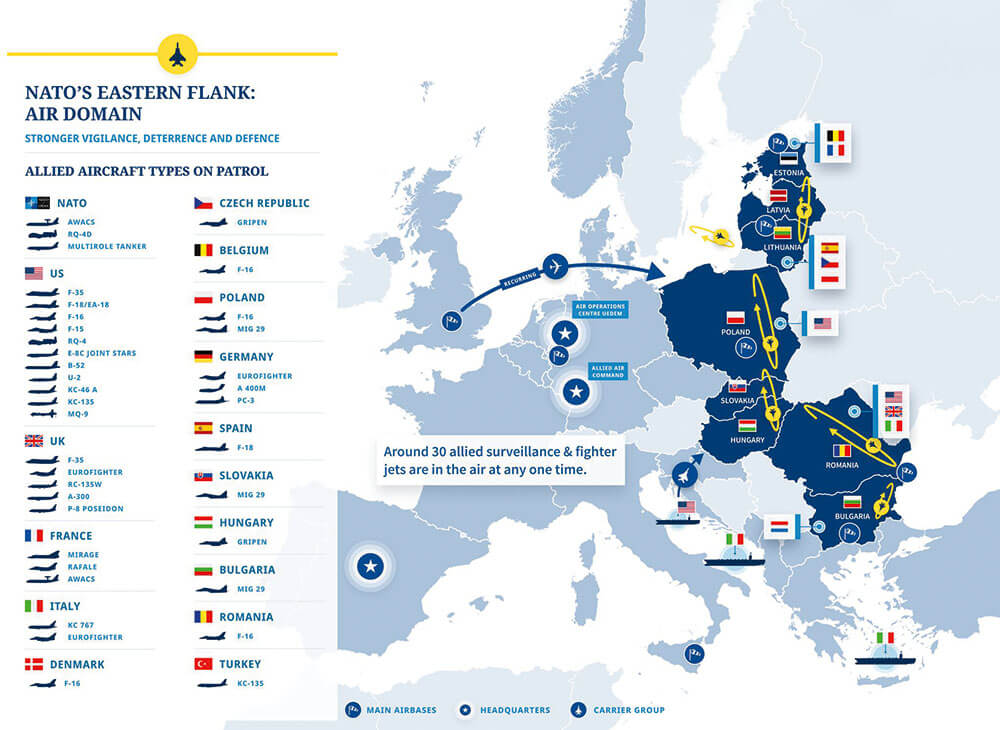

Following the commencement of the Ukraine conflict, NATO notably increased the presence of Air Power on its Eastern flank (as depicted in Figure 1 below), with the aim of denying Russia any opportunities to expand or escalate the ongoing conflict with Ukraine into a broader conflict involving NATO.

Figure 1: Air Domain activities.1

© NATO

Currently, NATO’s increased Air Power posture demonstrates the Alliance’s resolute determination to defend its territory against aggression while seeking to avoid escalation through effective deterrence.

However, these ‘new’ activities, including the increased posture, have been built upon plans and directives conceived years ago, in a vastly different strategic environment. While revision of old documents ensues, NATO has proven the viability by employing a comprehensive range of ready Air Power directly along its Eastern flank, spanning from the High North to the Southern regions of NATO’s territory, in a visible and impressive show of determination. Analysing observations and applying the NATO Lessons Learned Process from the RUS-UKR war is essential for capturing valid and practical best practices for the organization’s evolution. This process is already underway in real-time, with NATO adapting strategic documents, developing new plans, and reviewing key Air Power-related documents based on assessments.

The readiness level and posture of the Air Force is expected to be maintained as the ‘new normal’. This new normal must encompass a 360-degree approach, tailored to address threats originating from all strategic directions. As mentioned earlier, NATO is adapting plans, doctrines, and concepts to sustain this new normal, while also improving and adjusting its’ equipment and systems. For instance, the retirement of NATO’s Airborne Early Warning and Control System (AWACS) is planned for around 2035, after more than 50 years of service as NATO’s key surveillance and control asset. Recognizing its crucial role in the Alliance’s comprehensive defence, NATO has already initiated the Alliance Future Surveillance and Control (AFSC) project to acquire a follow-on capability. This project aims to develop options for future NATO surveillance and control capabilities, employing a system of systems that may involve a combination of air, ground, maritime, and space assets working together to collect and share information, facilitating a Multi-Domain Operational (MDO) approach. Designing and implementing such a complex and comprehensive architecture will take several months if not years to fulfil the requirements. The objective is to establish capable systems that are adaptable to a changing security environment, leveraging existing assets and fostering pragmatic Air and Space readiness, preparedness, and willingness for NATO’s future.

Space-Domain Readiness

The NATO space program forms the foundation for accessing Data, Products, and Services (DPS) provided by Alliance members, supporting a wide range of activities. The key aspect is that NATO enables essential space functionality across the Alliance but relies on the contributions of space-based DPS from various member nations.

NATO upholds the principles of free access and use of the space domain to serve the objectives of each nation’s space program. Ensuring space domain readiness within NATO entails securing the availability of space-based DPS for every member nation’s forces. While not all NATO members have developed their own space programs, through the Combined Forces Space Component and the NATO Space Centre, all Alliance members have access to space-based DPS benefiting war fighters and enabling NATO’s mission.

Nonetheless, achieving sustainable readiness in NATO’s Space domain is a complex and challenging endeavour that demands a comprehensive approach encompassing all readiness aspects, ranging from developing of new capabilities to personnel training. The development of new capabilities stands as a crucial facet of readiness, with NATO supporting national Space programs to foster internal resilience and provide Alliance-wide access to space-based DPS. NATO is actively developing the tools required to effectively receive and disseminate nationally contributed space-based DPS across all domains throughout the Alliance.

However, the paramount aspect of readiness lies in education and training personnel. NATO must prioritize the internal training of the Command and Force Structure to effectively utilize the space-based DPS contributed by member nations. This effort has become a top priority, evident through the integration of the Space domain into strategic exercises and the provision of space-centric training courses at the NATO School in Oberammergau. Additionally, the establishment of the NATO Space Centre of Excellence in Toulouse, France, further underscores the importance of the Space domain in NATO’s daily activities. While these steps mark significant progress, there is still much more to be accomplished.

Drawing lessons identified from the conflict in Ukraine, NATO must cultivate a culture of readiness that includes the Space domain as well. However, achieving sustainable space domain readiness is a long-term endeavour requiring unwavering commitment from both NATO and its member states. A unified effort is currently underway to enhance Space domain readiness, spearheaded by the Bi-Strategic Commands in collaboration with the NATO Space Centre of Excellence. Looking ahead, several specific issues must be addressed by NATO to further strengthen Space readiness:

- Continue building upon NATO’s nascent Space Power strategy. This strategy should continue to build-up NATO’s Space Power goals, and it should outline the steps that NATO should take to achieve those goals.

- Continue investing in new Space capabilities to exploit and disseminate nationally contributed DPS.

- Continue training and exercising personnel to use new Space capabilities.

- Exercise and evaluate NATO forces on using Space capabilities in combat.

- Continue developing a culture of readiness.

- Resolve classification and sharing issues among Nations and inside NATO.

- Set up the physical networks that will connect various national space centres with NATO and National HQs.

- Search for potential shared ventures to reduce cost and improve interoperability.

Overall, achieving and maintaining sustainable readiness in the NATO Space domain is a complex and challenging endeavour. Nevertheless, it is a crucial investment in the security of the Alliance. By implementing the steps outlined above, NATO can guarantee it possesses the necessary capabilities to deter aggression and protect its member nations.

Conclusion

As a military alliance, NATO has a crucial responsibility to provide credible deterrence and defence as the most effective means to prevent conflicts. To achieve this, NATO continuously adapts its Military Instrument of Power, while implementing the Concept for Deterrence and Defence of the Euro-Atlantic Area and the NATO Warfighting Capstone Concept. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has prompted the nations to take further steps in strengthening NATO’s readiness, demonstrating unwavering solidarity and determination.

In order to fulfil these objectives, NATO must undertake a thorough review and development of strategic documents and plans that have wide-ranging effects across the Alliance. This process aims to enhance NATO’s availability, readiness, and resilience across all domains. These adaptations to NATO’s Air and Space posture are aligned with the broader adaptation of the Alliance’s posture for deterrence and defence, maintaining a defensive and proportional approach.

The aggression displayed by Russia in Ukraine has emphasized the urgent need for NATO to improve its readiness effectively deterring potential adversaries. NATO is resolute in countering these threats, recognizing the various air and missile threats posed by Russia’s evolving capabilities, as well as the increasingly diverse and challenging threats from other state and non-state actors, including unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to advanced missile systems, including hypersonic missiles, in addition to more conventional threat.