Courtesy of the RAND Corporation.1 This is an excerpt from the main paper that can be accessed through www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2942.html.

Response Options for Coercive Aggression Below the Threshold of Major War

The 2017 US National Security Strategy and the publicly released summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy agree on one fundamental theme: The United States is entering a period of intensifying strategic competition with several rivals, most notably Russia and China. Numerous statements from senior US defense officials make clear that they expect this competition to be played out primarily below the threshold of major war – in the spectrum of competition that has become known as the gray zone.

Although such tactics as psychological warfare, subversion of political systems, and covert paramilitary and information operations are not new phenomena in international conflict and competition, our analysis shows that some of the tactics employed by Russia and China are comparatively new in form and effect. Moreover, the methods of gray zone coercion vary significantly between Russia and China and require differentiation of scope of threat posed to the United States, as well as types of potential responses. Both problems represent a strategic threat to US and allied interests, especially as techniques and technologies evolve over time. The United States and its allies, we find, have yet to come to terms with the challenge of the threat, let alone fashion a strategy to neutralize it or roll it back.

In this project, therefore, we aimed to provide a framework for conceptualizing the gray zone challenge and offer new policy options for the United States and its allies to consider in response. Despite the challenges involved, one finding of this research is that the United States can treat the ongoing gray zone competition more as an opportunity than a risk: By seeking to coerce, acquire influence within, or destabilize key countries and regions, Russia and China are opening the space for a vigorous US campaign to rally allies and partners in both regions in the direction of an effective response. This report uses insights from our extensive field research in affected countries, as well as general research into the literature on the gray zone phenomenon, to sketch out the elements of a strategic response to this challenge.

To inform such a response, we sought to (1) identify a potential strategic concept to govern a US strategy in the gray zone and (2) identify and evaluate a menu of specific response options. It is important to emphasize that the scope of this study is to offer a menu of options that could be of utility to US policymakers in both establishing a general strategy and choosing specific actions in response to gray zone tactics.

We do not seek to offer a judgment of the relative efficacy of specific courses of action for discrete gray zone events or an assessment of how the adversary may respond; this should be the objective of follow-on research. The study focused on Russian and Chinese gray zone activities and potential US and partner responses to them; we did not consider the gray zone tactics of other challengers.

Our primary source of information to support this analysis was an extensive program of field research in spring 2018. We traveled to Australia, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Poland, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and Vietnam to gather perspectives on the ongoing gray zone challenge. We also interviewed officials and scholars in Washington, D.C., including several from the Republic of Georgia, and we met with current and former national security officials, scholars, and researchers.

In addition, we reviewed the existing literature on gray zone challenges for possible response options, as well as the literature on deterrence for its possible lessons for the gray zone context. We relied on all of these sources of information to construct a potential strategic concept for gray zone competition and to inform our evaluation of specific response options.

The set of response options offered in this report is designed to offer an initial draft of a living document. The menu of options ought to be fleshed out and refined over time based on experience and further consultations. We do not pretend that the options offered here are comprehensive or optimal even now. And new ideas will emerge as the United States and its allies and partners gain more experience in this realm.

A Concept for Gaining Strategic Advantage in the Gray Zone

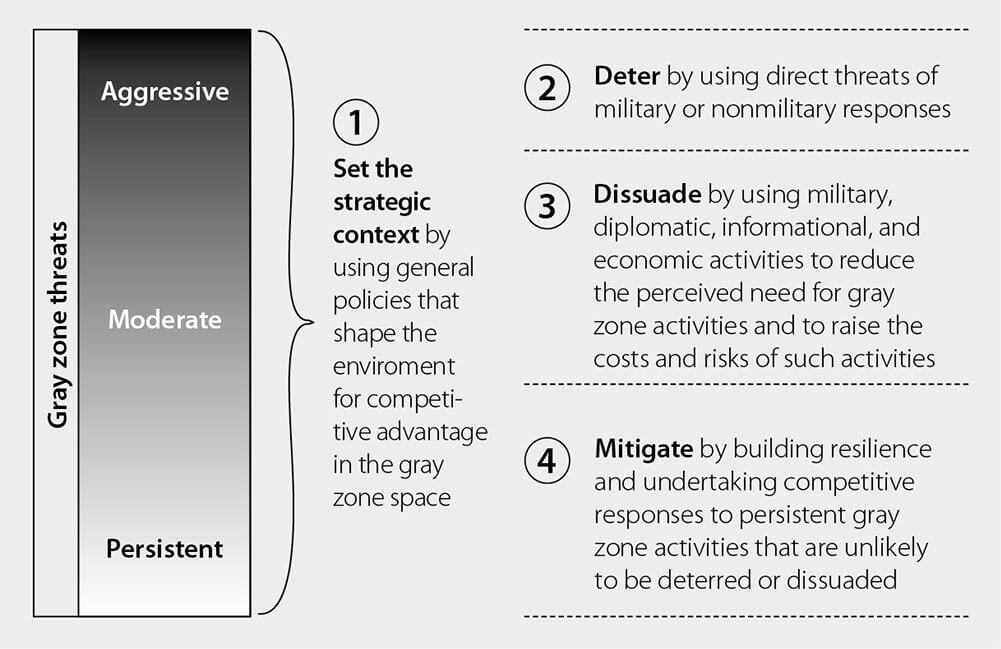

Not all gray zone activities are alike. Responses to more-aggressive gray zone activities will not necessarily mirror those of more-gradual, persistent initiatives. Any strategic concept for the gray zone therefore must distinguish among the various levels and design its responses accordingly.

Admittedly, the dividing lines between levels of gray zone tactics will not be precise or well defined in all cases. Rather, they are designed to convey three general conceptual ideas rather than three clearly defined baskets. The three general levels of gray zone activities are (1) aggressive actions, at one end of the spectrum, that the United States should seek to deter; (2) persistent actions, at the opposite end of the spectrum, that it must live with but can compete against; and (3) moderate actions in the middle that the United States should actively seek to discourage over time. As part of this study, we offer a specific framework for distinguishing levels of gray zone actions, and these distinctions then become the basis for the response concept.

Any division of gray zone activities points to one especially critical implication and a theme that our research suggests is essential to any US response strategy. The United States and its allies, partners, and friends must decide what actions they will resolutely not tolerate in the gray zone environment. Because of the difficulty in stopping gradual, sometimes unattributable actions involving secondary interests, identifying the actions that the United States will seek to deter is the one reliable way to draw a boundary around the possible effects of gray zone encroachment. With this conception of a spectrum of gray zone activity levels, we outline a four-part framework for responding to gray zone threats, shown in Figure S.1.

The proposed strategic concept for the gray zone has four major components. It first calls for a whole-of-government approach utilizing geopolitical, military, and economic actions to shape the strategic context. Second, it proposes that the United States should identify a small number of aggressive gray zone tactics to deter with explicit, credible threats of military or nonmilitary responses. Third, it seeks to dissuade a wider range of moderate gray zone activities over time. Finally, it calls for mitigating persistent threats by building a capability for resilience and competitive response to threats that cannot be deterred or dissuaded.

The remaining task for US strategists is then to draw on a rich menu of specific tools, techniques, and capabilities to formulate both ongoing and event-specific responses to gray zone provocations. As part of this study, we laid out a roster of such options. In the process, we did not attempt to build a scripted playbook that specified responses to every plausible Russian or Chinese action. The reality of gray zone competition is too fluid for that, and specific contexts will demand different responses to the same action. Instead, we aimed to assemble a menu from which US officials can choose in such situations, evaluating each potential response option according to three criteria: its potential advantages and benefits, its potential risks and costs, and other considerations derived from our research. In no case do we make a final evaluation of the advisability of any given option in a given situation; that will depend on the specific circumstances when each response takes place.

A multicomponent strategy like the one outlined here will be of limited utility if the US government continues to lack a clear coordinating function with the responsibility for overseeing a renewed effort to gain strategy advantage in the gray zone. An important part of any gray zone response strategy, therefore, is undertaking institutional reform. A major difficulty given the current organization of key US national security departments and agencies is that there is no single ideal home for a gray zone management function. The National Security Council is not an operational body, and it has a small staff devoted to coordinating policy rather than running multicomponent campaigns. The State Department has personnel and funding shortfalls and lacks interagency coordination authorities. It also often lacks an institutional mindset needed for aggressive countermeasures. Finally, placing a gray zone coordinating function solely at the Defense Department risks encouraging a dominant focus on military tools, which would not reflect the character of the challenge.

In considering alternatives for a fresh approach, we assessed two basic options. One can be described as the thin option and would use a presidentially directed strategy, perhaps issued in the form of a National Security Presidential Directive or other White House order, as the foundation of the approach. The order would outline the elements of a gray zone response concept and direct the actions of specific departments and agencies in support. It would then be coordinated by the National Security Council, under a senior director office devoted to the purpose.

Another alternative could be described as the thick option. This would assemble a more purpose-built office in the US government, with a significant devoted staff, to run counter–gray zone campaigns. It could be headed by a presidential special representative with the highest subcabinet rank and a direct reporting line to the president.

We looked at the National Counterterrorism Center for insights into launching a new, focused organization, although that model is designed to promote information-sharing and strategic operational planning more than the operational control of the strategy. This more elaborate option for institutional change could even include the development of regional implementation offices – the equivalent of military combatant commands – to run the gray zone campaigns in those areas (at a minimum, in Europe and Asia).

Whatever option is chosen, the US government can take several accompanying steps to give the gray zone strategy the necessary profile in national security planning. These steps include the following:

- Make the issue a special focus in state and Defense Department regional offices, ensuring the necessary staff support to track evolving gray zone activities on their own terms.

- Require that responses to gray zone activities be included as a prominent theme in relevant embassy country strategies.

- Require military service initiatives to emphasize gray zone issues in, for example, career development; training and education; and the funding and support for technologies, capabilities, and experimental force design and concepts tailored to the gray zone.