Space Development in the South America Region

South America as a geographical region and the individual nations, have traditionally been exploited by global powers because of their global position and abundant natural resources. However, South America is also challenged because it has not been able to develop a regional governance structure due to difficulties with regards to integration and collaborations between the various countries. These difficulties originate from unresolved territorial conflicts and the challenges from generalizations that all the countries remain in the category of ‘undeveloping’ with one huge heterogeneous population.

At the beginning of the Space Race, space activities in South America, remained under national control, being part of international organizations as The Committee for Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS), signatories of Corpus Iuris Spatialis and then part of the Office of Outer Space Affairs of United Nations (UNOOSA). Also, due to previous historic interactions, there is evidence of early cooperation with Space Powers.1

In the 1980s, Chile started with the development of indigenous space capabilities. This was accomplished in the context of national control, specifically Chile’s authoritarian government and its links to the army. The vision at the government level involved the understanding of outer space as a new domain for military operations, and a way to reach local superiority and not be vulnerable in a potential local conflict.2

With the end of ‘pax Americana era’ in the 2001, and the decrease of entry barriers to space technology, the region began to acquire space capabilities3, but the technological gap (product of technology evolution) revealed the necessity to cooperate with a ‘Space Power’4 in order to acquire knowledge, technology and experience. However, the technological transference, even the acquisition of technological systems and knowledge, involved the mechanisms of international cooperation. The relevant element for the analysis on space development within the region remains the formulation of the normative infrastructure. This meant space policies, laws, and infrastructure were somewhat organically created, because of the defined goals and vision of the State concerning space development and was a sign of how the region moved into the new century.

Why South America Remains a Relevant Geographical Zone

Throughout more than 60 years of development, Space-based capabilities have demonstrated their great influence in geopolitical processes through a direct relation between the increase of human dependence on Space-related technologies and the globalization of communications and information sharing capabilities. In this sense, Space infrastructure becomes critical to the development of day to day activities around the world; to include planning for economic development, urban growth, and military mobilization.

Space-related technologies have allowed for more effective action from the central planning of nations, involving the decrease of expenditures and allowing for a more rational public investment. With a better use of public resources, nations have been able to re-distribute public expenditures and begin to develop solutions to significant public challenges related to social infrastructure and the resilience of society. That is why nations look to Space, and over time Space has been increasingly recognized as a domain and a natural extension of international system5.

The absence of an existing Space infrastructure in the southern hemisphere, created an opportunity and competition among Space Powers to secure ground infrastructure to support their Space missions and requirements, usually through traditional mechanisms of collaboration with host nations. In this new era of Space Powers, South America is highlighted in importance because the geographical position of the region allows the tracking of satellites through their orbits over the southern hemisphere, improving mission safety and security. In addition, the region contains natural resources crucial to advanced technologies which are of keen interest for Space Powers.

This new era of geopolitical interest represents an opportunity for South American Nations to increase their own national power and prestige through Space activities. These nations have found a chance to reduce the technology gap by gaining access to Space-related capabilities in order to improve their national infrastructures through collaboration and trade with Space Powers.

As South America enters a process of acquisition of Space technology based upon their individual national interests, most of them have adopted space policies, laws, and organic infrastructure created to host the newly acquired capabilities. However, as the influence of United States has decreased in the region, other nations have emerged with offers of agreements and access to products that provide them greater influence across South America. This shift in influence by global power within South America, driven by Space-related technologies and capabilities, has carried over into other elements of influence and cooperation as shown in the adjacent picture.

From the image, which depicts projects pertaining to space capabilities, it is easy to conclude that there is a strong Chinese presence in the region, to the detriment of United States’ influence on similar activities. In addition, there is strong evidence to conclude China has leveraged these agreements to obtain access to other strategic resources,7 interoceanic trade, and developments related to nuclear capabilities.

The increasing presence of Chinese interests in South America related to Space matters also has revealed deep connections to military Space activities, this form of technological transfer could have significant impact on the balance of power within the region, which can be traced through the formulation of Space-related policies in the various nations.

Space Policy Formulation: Signs of Changes in Powers Balance Emerge of Old Geoconflicts

In order to capture the development of the region in terms of changes to power balances, this paper will be focused on a review of six study cases: Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Perú, and Venezuela. The selection of these cases considered the logic of non-probabilistic selection utilizing the following criteria:

- A States in possession of at least one Space system under national administration for the last eight years.

- B States with at least one public instrument to regulate national Space activities.

- C States with at least one active territorial dispute.

- D States that are members of geographical zone of South America.

- E States with at least one reserve of geostrategic natural resources.

With regards to the nations’ purposes for engaging in Space activities, in case studies, the nations relied upon a public policy instrument that focused Space activities into one of the following terms: country development, improvement of their position within the international order, or improvements related to some national planning priorities8. This is relevant because it reveals the intentional increase of capabilities from the nations based on the incorporation of space technology9. Also, there is no evidence of the inclusion of ‘peaceful uses’ terminology into the formulation of public policies. Instead, the principle of good faith10 of any actor is accomplished through international compromises acquired by the corpus Iuris Spatialis.

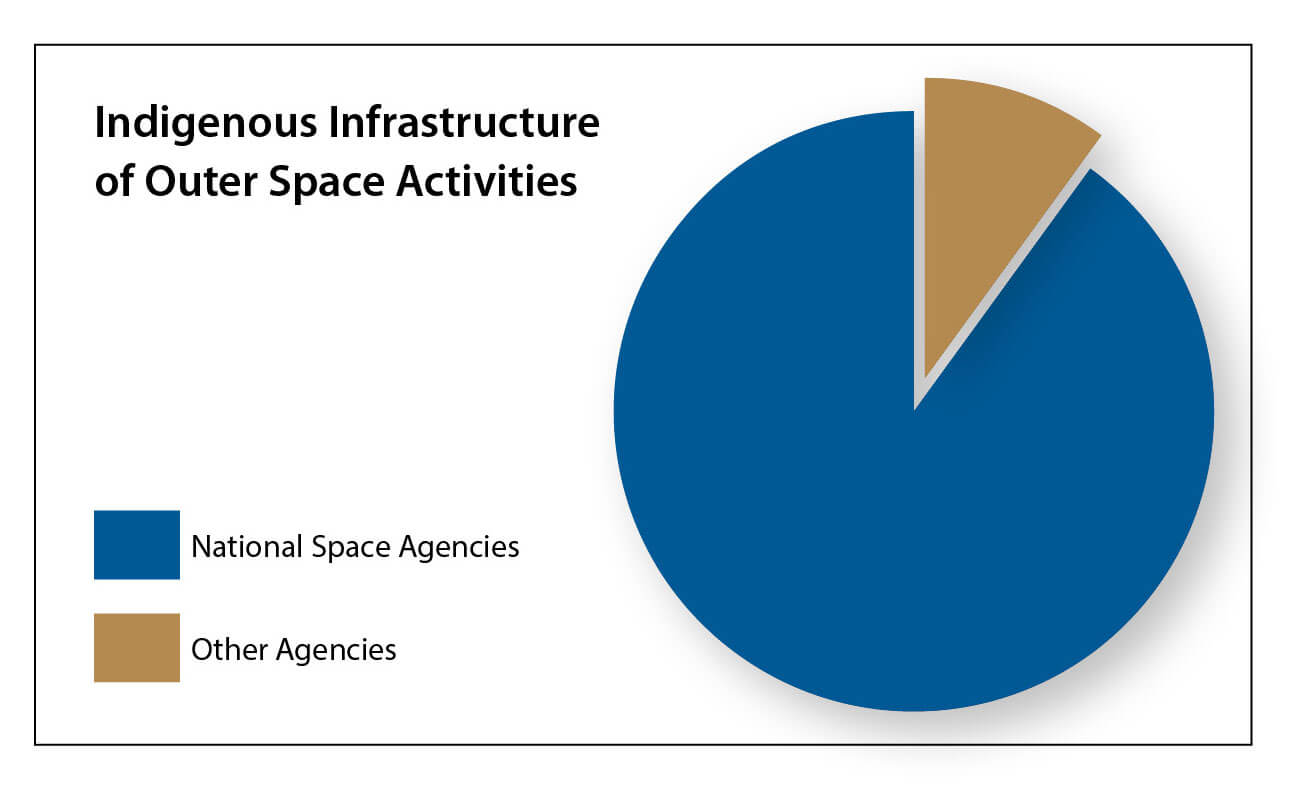

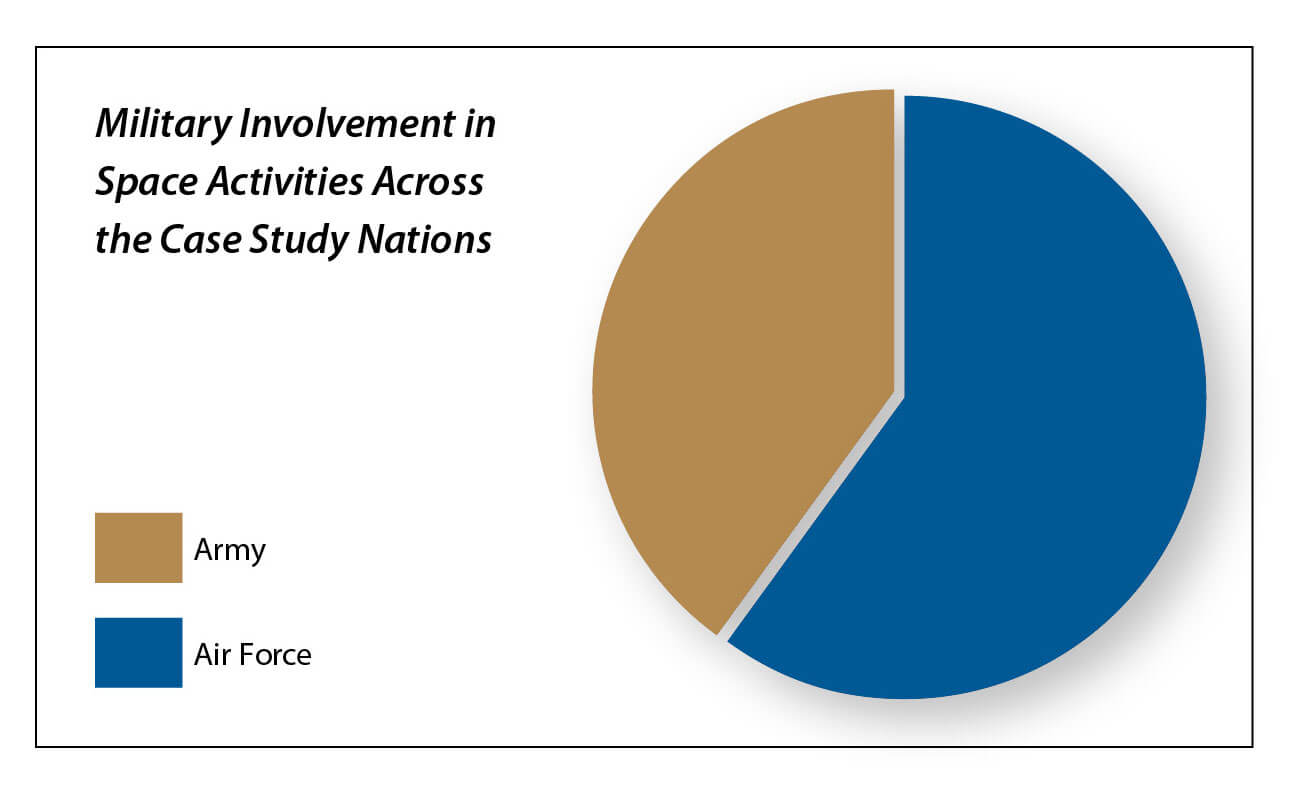

Based on an analysis of indigenous infrastructures of existing Space organizations, with some form of active space capabilities, the evidence shows that in the majority of cases militaries are involve in these activities, in some cases exerting significant influence on the processes and activities. This also means national Space capabilities within South America are often considered to be dual-use capabilities, regardless if the principal declared mission is for civil purposes. This link with militaries indicates that Space systems contribute to defence sector and are susceptible to being considered as weapon systems.

Finally, as the evidence showed Space capability links with the defence sector, the research continued for evidence of policies formulated related to supporting these activities. In each case, there is ample evidence of formulation of these types of policies related to Space systems. The result in each case study, therefore, is formulation of employment concepts and modernization of militaries in order to incorporate Space-based technology into their daily duties. Additional evidence for this assertion is found in evidence of Space capability and/or technology-related training of military forces.

Foresight and Challenges for Peaceful Uses of Outer Space

The study of normative policies and technology acquisition of countries in South America has reveal that modernization of associated battlefield capabilities is not only given by the indigenous development of those capabilities, but also is influenced by international players. In this sense, there is no evidence that the status quo of space activities will remain if the international situation shifts from traditional powers. In the case study, there is a strong tendency to move from traditional relationship in search of new allies, motivated by increased incentives for collaboration in order to acquire more advanced technological components which that can have a positive impact in their domestic power. Regardless of previous relationships, the evidence shows that the technological cooperation with actors, like China has improved the Space programs within the region. Even more, there are countries that have a Space program derived entirely from collaboration with China.11

Specifically, countries in the region have demonstrated the ability to identify Space-based technology as dual-use assets, improving all their instruments of national power. Brazil and Bolivia, in particular, are more resilient in the face of new hazards and security challenges than either were just ten years ago.

Admittedly, not all states reach the same level of influence within their respective regions or within the larger international community. There are some nations, such as Brazil and Argentina, that are seeking a position of regional leadership, and there are also cases, like Bolivia, in which the focus is on gaining the upper-hand in small-scale cross-border conflicts.

Regardless of the level of influence sought, the modernization of one nation into new domains (such as Space) changes the terms of engagement and stimulates their neighbours to ensure what they see as the proper balance the power. Due to security implications exacerbated by active territorial controversies, these changes in power dynamics can involve all nations in the region into an escalation of Space Power development.

From the outside looking in, this dynamic in South America can be seen is profitable to new actors with global aspirations, such as China, because of perceived lower associated costs. These actors believe the shifting power dynamics allow them easier access to influence a new region, access made easier by the decline of traditional cultural norms and other indicators of soft power of traditional powers. At the same time, more influence in the region means more opportunities to access strategic geographical zones thus improving their own capabilities, like command and control of lunar missions, and contributing to their national goals.

Finally, based on traditional geopolitical dynamics, the collaboration between some South American Nations and China, as it pertains to Space, should be seen as a short-term relationship. This is because the origin of these collaborations is linked to the reduction of the technology gap in these nations, so they might increase their national power. This means that in the long-term, in order to maintain these relationships, China will need to provide additional stimulus to indigenous Space capability development in order to maintain a relationship. All the while, there are new Space Powers emerging who might offer a better deal, with lower costs with regards to exploitation of natural resources (that will be demanded by their own space industries process) and more acceptable terms with regard to issues related to national sovereignty.

Ultimately, the use of Space, and its associated technologies, for any nations remains focused on national goals and desires with regards to the needs associated with a Space Program. The Space domain is like any other domain, in that how it is seen and utilized has an impact on National Power, because it is linked to social dynamics between society and perceived technological benefits. Changes in social dynamics, including those from small to large scale conflicts, will be increasingly affected by space activities and eventually multi-domain operations as technological advances are realized.

The existence of states without indigenous Space capability is only evidence of the economic gap that exists in some regions, but should not be confused with a lack of interest of those nations in realizing the benefits from space capabilities in order to increase their respective national power, particularly through military applications, as these portend security and reduce uncertainty in potential future conflicts.